Supported by

What to Know About Ukraine’s Cross-Border Assault Into Russia

The incursion caught Russia by surprise and signified a shift in tactics for Kyiv after more than two years of war with Russia.

Ukraine pressed ahead with its offensive inside Russian territory on Sunday, pushing toward more villages and towns nearly two weeks into the first significant foreign incursion in Russia since World War II.

But even as the Ukrainian army was advancing in Russia’s western Kursk region, its troops were steadily losing ground on their own territory. The Russian military is now about eight miles from the town of Pokrovsk in eastern Ukraine, according to open-source battlefield maps. The capture of Pokrovsk, a Ukrainian stronghold, would bring Moscow one step closer to its long-held goal of capturing the entire Donetsk region.

That underscored the gamble Ukraine’s army took when it crossed into Russia: throwing its forces into a daring offensive that risked weakening its own positions on the eastern front.

Whether that strategy will prove advantageous remains to be seen, analysts say.

On the political front, the offensive has already had some success: Ukraine’s rapid advance has embarrassed the Kremlin and has altered the narrative of a war in which Kyiv’s forces had been on the back foot for months.

Here’s what to know about Ukraine’s cross-border operation, which President Biden said last week was creating a “real dilemma” for the Russian government.

What happened?

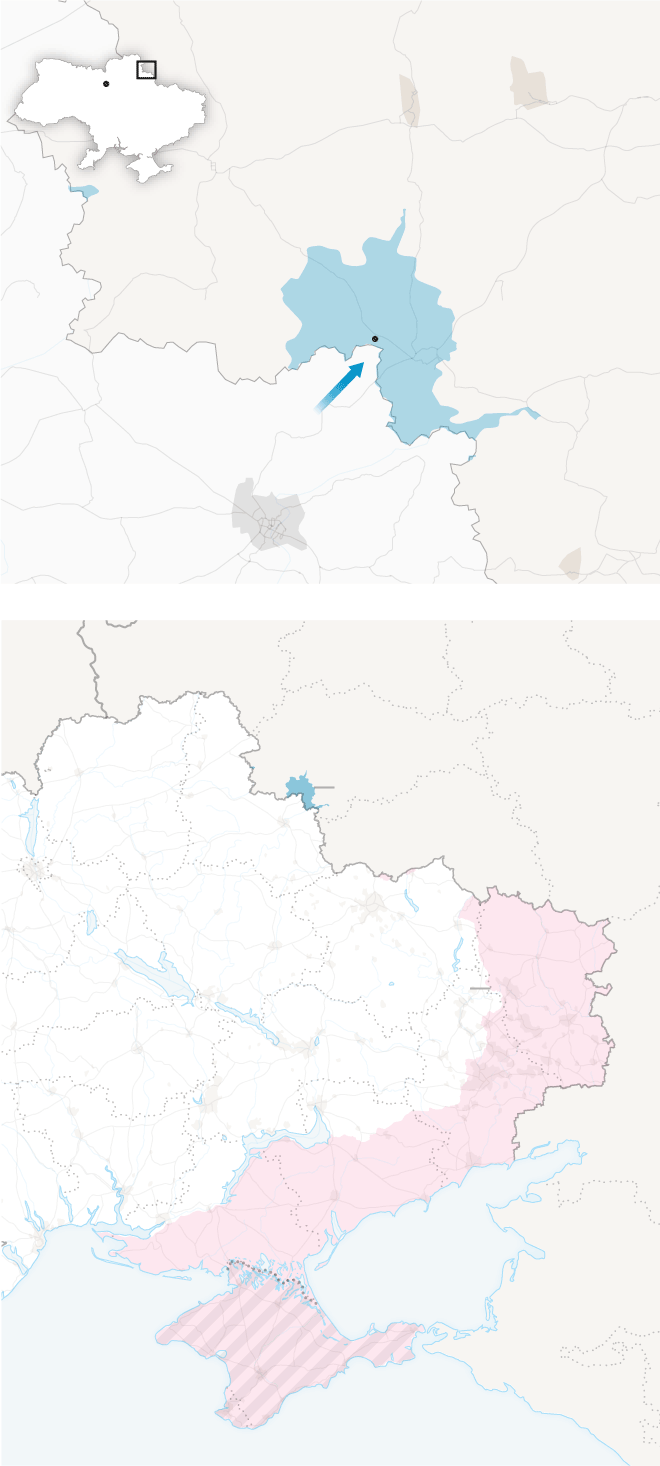

Ukrainian troops and armored vehicles stormed into the Kursk region of western Russia on Aug. 6, swiftly pushing through Russian defenses and capturing several villages.

Area shown

Kurchatov

Kyiv

Lgov

UKR.

Held by Ukraine

as of Aug. 13

RUSSIA

Sverdlikovo

Ukrainian

incursion

UKRAINE

Sumy

10 miles

RUSSIA

Ukrainian

incursion

Nizhyn

Sumy

Kyiv

Kharkiv

Izium

Sievierodonetsk

UKRAINE

Area controlled

by Russia

Luhansk

Dnipro

Donetsk

Kryvyi Rih

Voznesensk

Zaporizhzhia

Mariupol

Mykolaiv

Melitopol

Kherson

Odesa

Sea of Azov

CRIMEA

Black Sea

50 miles

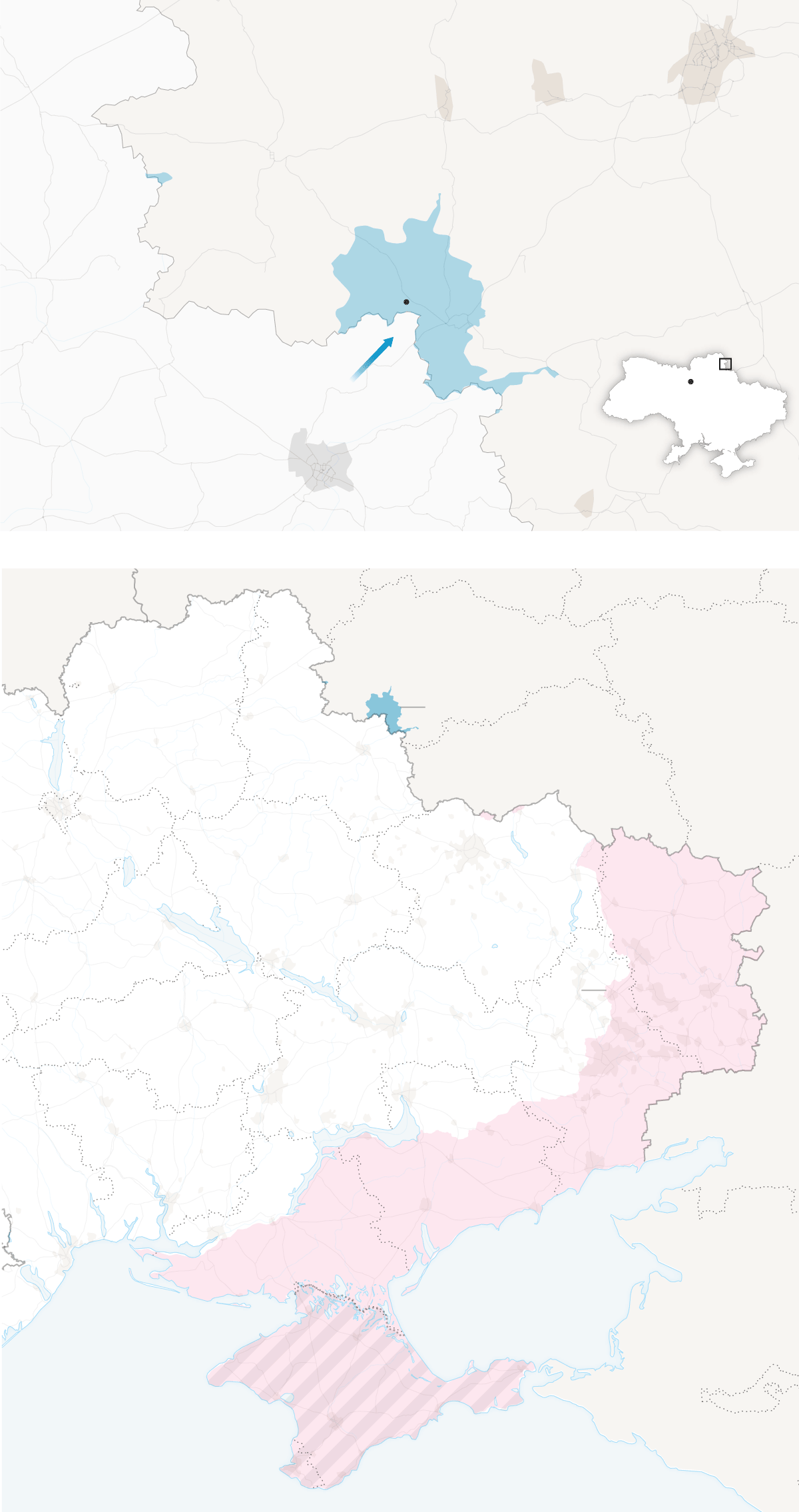

Kursk

Kurchatov

Lgov

Held by Ukraine

as of Aug. 13

RUSSIA

Sverdlikovo

Area shown

Kyiv

UKRAINE

Ukrainian incursion

UKR.

Sumy

10 miles

RUSSIA

Ukrainian

incursion

Nizhyn

Sumy

Romny

Brovary

Kyiv

Kharkiv

Izium

UKRAINE

Sievierodonetsk

Luhansk

Area controlled

by Russia

Dnipro

Donetsk

Kryvyi Rih

Zaporizhzhia

Mariupol

Mykolaiv

Melitopol

Kherson

Odesa

Sea of Azov

CRIMEA

Black Sea

50 miles

Source: Institute for the Study of War with American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project

By Veronica Penney

The assault, prepared in the utmost secrecy, opened a new front in the 30-month war and caught not only Russia off guard: Some Ukrainian soldiers and U.S. officials also said they lacked advance notice.

Analysts and Western officials estimate that Ukraine deployed about 1,000 troops at the start of the incursion. But military analysts say that it has since poured more troops into the operation to try to hold and expand its positions.

How far into Russia have Ukrainian troops advanced?

Gen. Oleksandr Syrsky, Ukraine’s top commander, said last week that his army now controlled more than 80 Russian settlements in the Kursk region, including Sudzha, a town of 6,000 residents. His claims could not be independently verified, although analysts say that Sudzha is highly likely to be under full Ukrainian control.

Ukraine’s advance in the Kursk region has slowed in recent days, according to open-source maps of the battlefield based on combat footage and satellite images, as Russia sends in more reinforcements. The Ukrainian army appears to be trying to dig in along the border area rather than pushing deeper into Russia.

President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine acknowledged that on Saturday, saying: “Now we are reinforcing our positions. The foothold of our presence is getting stronger.”

Why is this significant?

Kyiv has regularly bombarded Russian oil refineries and airfields with drones since Moscow’s full-scale invasion began in February 2022. It has also helped stage two other ground attacks in Russia. Those, however, were smaller forays by Russian exile groups backed by the Ukrainian army, and they ended in quick retreats.

Until two weeks ago, Ukrainian forces had not counterattacked in Russia. The gains in Kursk are the quickest for Ukrainian forces since they reclaimed the Kherson region of their own country in November 2022.

How has the Kremlin responded?

As Ukrainian forces pushed deeper into Russia, Moscow scrambled to shore up its defenses, and President Vladimir V. Putin convened his security services to coordinate a response. The Russian military said it was sending more troops and armored vehicles to try to repel the attack, with Russian television broadcasting images of columns of military trucks.

Military analysts and U.S. officials have said the Russian command had so far brought in reinforcements mainly from within Russia so as to not deplete its units on the Ukrainian battlefield, in what they described as a disorganized effort.

“Russia is still pulling together its reaction,” Gen. Christopher G. Cavoli, NATO’s top military commander, said last week during a talk at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. He described the Russian response as having been “fairly slow and scattered” as the authorities sorted out which military and security forces should take the lead.

And what about Putin?

The incursion has embarrassed Mr. Putin and his military establishment, prompting questions about Russia’s level of preparedness.

Underscoring how the attack rattled the Kremlin, Mr. Putin lashed out last week at the West in a tense televised meeting with his top officials. “The West is fighting us with the hands of the Ukrainians,” he said, repeating his frequent depiction of the war, which he started, as a proxy campaign against Russia by the West.

Ukraine’s incursion has brought the war into Russia like it never has before, and tens of thousands of civilians have evacuated the border area.

What is the goal of Ukraine’s incursion?

Analysts say that Ukraine’s offensive has two main aims: to draw Russian forces from the front lines in eastern Ukraine and to seize territory that could serve as a bargaining chip in future peace talks.

Mykhailo Podolyak, a top Ukrainian presidential adviser, said last week that Russia would be forced to the negotiating table only through suffering “significant tactical defeats.”

“In the Kursk region, we can clearly see how the military tool is being used objectively to persuade” Russia to enter “a fair negotiation process,” he wrote on social media.

The operation has offered a much-needed morale boost for Ukrainians, whose forces have been losing ground to Russian troops for months.

But military analysts have questioned whether Kyiv’s cross-border assault is worth the risk, given that Ukrainian forces are already stretched on the front lines of their own country.

How is it affecting the fight inside Ukraine?

Russian forces have been pummeling Ukrainian troops in the east even as Moscow races to respond to the incursion into Kursk, according to analysts, Western officials and Ukrainian soldiers.

Russia has begun to withdraw small numbers of troops from Ukraine, they said, to try to help repel the Ukrainians, but not enough to significantly affect the overall battlefield for now.

Senior American officials have said privately that they understood Kyiv’s need to change the narrative of the war, but that they were skeptical that Ukraine could hold the territory long enough to force Russia to divert significant resources from the front lines in eastern and southern Ukraine.

While Kyiv’s allies have in the past been wary that Ukrainian incursions in Russia could escalate the war, the European Union’s top diplomat, Josep Borrell Fontelles, said last week that Ukraine had the bloc’s “full support.”

Ukraine has used some Western-supplied weapons in the Kursk operation. But so far, the United States and Britain, two of Kyiv’s closes allies, have said the incursion did not violate their policies.”

What happens next?

As the Ukrainian offensive approaches its two-week mark, analysts say that Kyiv has several options, each with its own challenges.

Ukrainian forces could try to keep pushing farther into Russia, but that will become harder as Russian reinforcements arrive and Ukraine’s supply lines are stretched.

They could keep digging into the territory they now hold and try to defend it, but that could expose fixed Ukrainian positions to potentially devastating Russian airstrikes.

Or, battered by continual losses in eastern Ukraine, they could decide that they have made their point and pull back.

Thibault Fouillet, the deputy director of the Institute for Strategic and Defense Studies, a French research center, said Ukraine’s next move would depend on how Russia responds. “The coming week will be decisive,” he said.

Eric Schmitt contributed reporting.

Andrew E. Kramer is the Kyiv bureau chief for The Times, who has been covering the war in Ukraine since 2014. More about Andrew E. Kramer

Constant Méheut reports on the war in Ukraine, including battlefield developments, attacks on civilian centers and how the war is affecting its people. More about Constant Méheut

Kim Barker is a Times reporter writing in-depth stories about national issues. More about Kim Barker

Anton Troianovski is the Moscow bureau chief for The Times. He writes about Russia, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. More about Anton Troianovski

Advertisement