Supported by

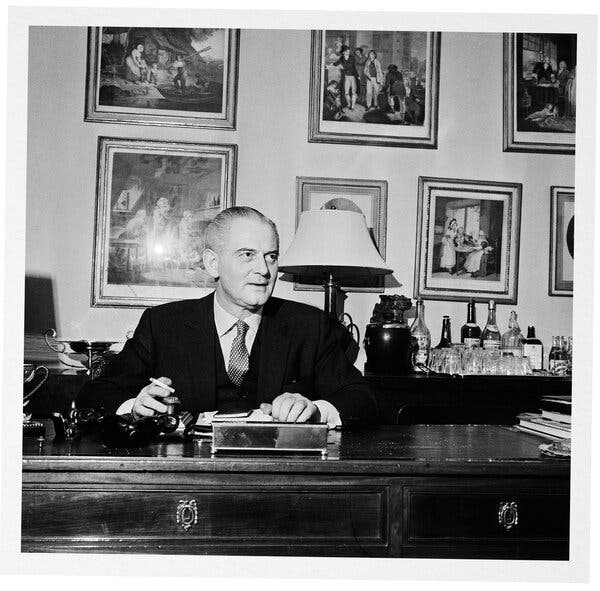

Overlooked No More: Otto Lucas, ‘God in the Hat World’

His designs made it onto the covers of fashion magazines and onto the heads of celebrities like Greta Garbo. His business closed after he died in a plane crash.

This article is part of Overlooked, a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times.

To many fashionable women in the mid-20th century, no hat was worth wearing unless it was made by Otto Lucas.

A London-based milliner, Lucas designed chic turbans, berets and cloches, often made from luxe velvets and silks and adorned with flowers or feathers.

His designs made it onto the covers of magazines like British Vogue and onto the heads of clients who reportedly included the actresses Greta Garbo and Gene Tierney, as well as the Duchesses of Windsor and Kent.

The name Otto Lucas was ubiquitous in England. At the height of his success, he sold thousands of hats each year around the world.

“He must have been the most famous milliner of the ’60s,” Philip Somerville, an assistant to Lucas who later designed hats for Queen Elizabeth II, told The Liverpool Echo in 1984. “His name was God in the hat world.”

Yet even as his sharp instinct for style and trends made him a pre-eminent name in millinery, he struggled as a German-born Jew in World War II-era Britain, and as a gay man in a country that criminalized homosexual acts. He lived something of a double life, flaunting a glamorous lifestyle to the outside world while privately seeking out safe havens for queer people.

Otto Lucas was born on July 9, 1903, in Mülheim, Germany, to Jacob and Dina Lucas, both German Jews. His father was a horse trader. He had a sister, Erna.

Details about Lucas’s early life are scarce, but the scholar Anna Nyburg wrote in “The Clothes on Our Backs: How Refugees From Nazism Revitalised the British Fashion Trade” (2020) that he trained as a milliner in Paris and might have worked in Berlin before moving to London around 1932. Three years later he was running a successful shop on New Bond Street, known for its high-end boutiques.

With the outbreak of World War II, about 70,000 Germans and Austrians, many of them Jews, were classified as “enemy aliens” under the British government.

Lucas’s parents, who left Germany for the Netherlands in 1936, were deported to Auschwitz in 1943 and were killed there soon after. Lucas was interned at a camp on the Isle of Man from June to September 1940.

Once the war ended, Lucas’s international reputation exploded. He was exporting shipments of hats to Australia by 1946, and he began traveling to showcase them, earning international attention.

“I think of all beautiful women” when designing hats, Lucas told United Press International in 1948. “Any woman in the world could wear them.”

While he was on a trip to the United States in 1948, The New York Times described some of his creations: “a black taffeta, worn level on the head and massed with bows at the back”; a bonnet made of “green and pink striped satin” with “roses nestling at one side.”

The Los Angeles Times reported that Lucas, “Bond Street’s mad hatter,” sold 103 hats in two days at Saks Fifth Avenue.

“What makes Otto Lucas’s hats different?” The Philadelphia Inquirer asked in 1953, adding, “There’s no doubt about it, his hats have elegance but with a disarming kind of charm.”

Lucas described his method succinctly to The Sydney Morning Herald in 1955: “I regard hat-making as an art and a science.”

In 1961, Lucas became a naturalized citizen of England, where he supplied hats to high-end department stores like Harrods and Fortnum & Mason, started a fast-selling line of more affordable hats called Otto Lucas Junior and showed his creations at London Fashion Week.

“Hats are my mad extravagance, I buy several a year from Otto Lucas,” Beryl Maudling, a former actress and dancer, told The Daily Herald in 1963. “But when you are as small as I am, an important hat is essential — gives you ‘presence.’”

Lucas designed special editions of hats to celebrate Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953, giving them names like “Tiara,” “Dream Princess” and “Crown Jewels,” and he created lines for female athletes during the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome and the 1964 Summer Games in Tokyo.

By the 1950s, he had a staff of more than 100 people, including three designers who were usually hired from Paris.

Carole Cornish, a graphic designer who made hats for Lucas in 1964 and 1965, said in an interview that he was “very smart” and “not unpleasant,” but that he could be particular. “There would be arguments if the designer wanted to do something and he didn’t,” she said.

But, Cornish said, working at his business could be exciting, particularly when royalty visited the showroom. “We did feel quite privileged that we were working for such a high-powered man,” she said.

It all translated to enormous financial success. Rolf Andersen, Lucas’s partner for about 10 years, told Nyburg in an interview for “The Clothes on Our Backs” that Lucas wore custom suits, drank lots of Champagne and was chauffeured around in a Rolls-Royce. The couple lived in a swanky area of London with two poodles, Olga and Whisky, and had a country home in Kent, in southeast England, with acres upon acres of lavish gardens.

Though homosexual acts were criminalized in Britain until 1967, Cornish said that she and others who worked for Lucas were aware that he was gay. Lucas was also a mainstay at the Colony Room Club, a haunt for artists and bohemians in the Soho neighborhood of London that welcomed gay men and lesbians, and he was a close friend of the owner, Muriel Belcher, a lesbian who was fairly open about her own sexuality.

Lucas died in a plane crash in Belgium on Oct. 2, 1971, while en route from London to Salzburg, Austria. All 55 passengers and eight crew members were killed, according to news reports, after a mechanical failure. Lucas was 68.

A posting in a British newspaper announced that Lucas’s assets, totaling about 150,000 pounds after taxes (about $2.3 million in today’s dollars), were left to Andersen. His business was liquidated in 1972.

By some estimates, Lucas sold 55,000 hats in his last year of business, said Lucie Whitmore, the lead curator of “Fashion City,” an exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands about Jewish contributions to British fashion that included a section about Lucas. His creations can still be found at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and they sometimes pop up on eBay. But for the most part, Whitmore said, after his death, “his name disappears really quickly.”

Lucas might not have been surprised by this.

“Fashion goes forward with the times,” he told The Morning Herald in 1960. “It is vivid, vital, ever-changing. We milliners are not concerned with anything that happened yesterday.”

Overlooked No More

Since 1851, white men have made up a vast majority of New York Times obituaries. Now, we’re adding the stories of other remarkable people.

Renee Carroll: From the cloakroom at Sardi’s, she made her own mark on Broadway, hobnobbing with celebrity clients while safekeeping fedoras, bowlers, derbies and more.

Lizzie Magie: Magie’s creation, The Landlord’s Game, inspired the spinoff we know today: Monopoly. But credit for the idea long went to someone else.

Henrietta Leavitt: The portrait that emerged from her discovery, called Leavitt’s Law, showed that the universe was hundreds of times bigger than astronomers had imagined.

Miriam Solovieff: She led a successful career as a violinist despite coping with a horrific event: witnessing the killing of her mother and sister at the hands of her father at 18.

Beatrix Potter: She created one of the world’s best-known characters for children and fought to have the book published, but she never sought celebrity status.

Cordell Jackson: A pioneering record-label owner and engineer, she played guitar in a raw and unapologetically abrasive way.

Advertisement