Supported by

Overlooked No More: Lorenza Böttner, Transgender Artist Who Found Beauty in Disability

Böttner, whose specialty was self-portraiture, celebrated her armless body in paintings she created with her mouth and feet while dancing in public.

This article is part of Overlooked, a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times.

It was the weekend of the gay pride parade in New York City in 1984 when Denise Katz heard her doorbell ring. Surprised, she opened her door and was greeted by Lorenza Böttner, a transgender artist, who was wearing a wedding gown that she had customized to fit her armless body.

“I’m here for the party!” Böttner said in her hybrid German-Chilean accent. Though Böttner had buzzed the wrong apartment, Katz invited her in anyway. “From that moment on, we didn’t part,” she said.

That Katz worked in an art supply store and Böttner was a prolific artist was pure coincidence.

Throughout her lifetime, Böttner created a multidisciplinary body of work with her feet and mouth that included painting, drawing, photography, dance and performance art. She made hundreds of paintings in Europe and America, dancing in public across large canvases while creating impressionistic brushstrokes with her footprints. In New York, she performed in front of St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, and Katz, who would become her roommate, provided her with large pieces of paper and other supplies.

Though Böttner did not achieve mainstream fame in her lifetime, her oeuvre — which criticizes both gender norms and the concept of disability — has in recent years been recognized as a significant contribution to the art-historical canon, in part for its radical representation of atypical bodies.

Böttner’s work has gained further visibility through a traveling exhibition, “Requiem for the Norm,” curated by Paul B. Preciado, a transgender writer and philosopher.

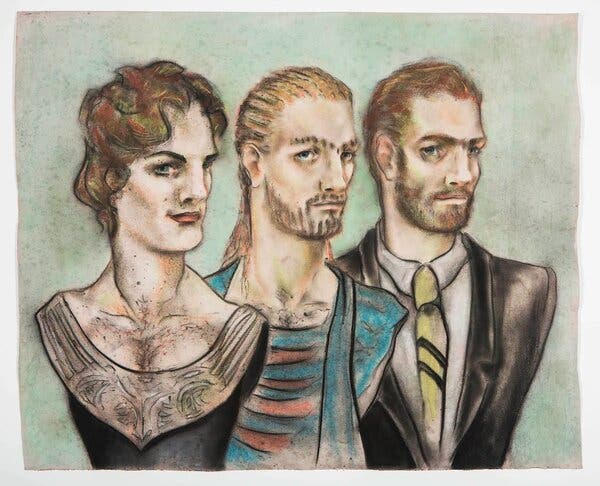

In her self-portraiture, Böttner celebrated and eroticized her form and depicted herself as a multitude of gender-diverse selves. In a photo series called “Face Art,” she used makeup to undergo a process of metamorphosis with masks that emphasized and distorted some of her features.

Böttner also transposed her face and body into stereotypical depictions of women throughout art history — rendering herself, for example, as a ballerina or a mother nursing a child. In one work, “Venus de Milo,” Böttner’s body was cast and turned into a sculpture that emulates the famous Greek statue.

“I wanted to show the beauty of the crippled body,” she said in a short documentary about her life, “Lorenza — Portrait of an Artist” (1991). “I saw how many statues were admired for their beauty and, through an accident, they too had lost their arms — but have lost nothing of their aesthetic appeal.”

Lorenza Böttner was born into a family of German migrants on March 6, 1959, in Punta Arenas, in southern Chile, and was assigned male at birth. She was a precocious child who showed an early talent for art — and an affinity for birds.

When she was about 9, she climbed a transmission tower in hopes of locating a nest and finding a baby bird to keep as a pet. Startled by a mother bird who suddenly opened her wings, Lorenza lost her balance and grabbed the live electrical cables hanging around her to avoid falling. Her arms were both severely burned up to the elbows and ultimately amputated at the shoulders.

In 1969, she relocated to Germany with her mother, Irene Böttner, who held various jobs, including working in a bakery and cleaning houses. Lorenza was treated at the Heidelberg Rehabilitation Center and educated at the Lichtenau Orthopedic Rehabilitation Clinic, Preciado said. She struggled through her recovery and, to the dismay of her doctors, rejected the use of prosthetic arms.

“As a teen, Lorenza was depressed and apathetic and tried maybe more than once to commit suicide,” Katz said in an interview. “It was her mother, Irene, who put the pen in Lorenza’s mouth, and put the will to live through art into Lorenza.”

From 1978 to 1984, Böttner studied art at the Gesamthochschule Kassel, where self-portraiture became a cornerstone of her artistic practice. Her interest in performance was nurtured during her studies, and she developed a hybrid form of expression that she called “danced painting” (“tanz malerei” in German) or “pantomime painting” (“pantomime malerei”).

After graduating in 1984, Böttner moved to New York City to study dance and performance at New York University with a grant from the Disabled Artists Network. She frequented nightclubs and roller-skating rinks and was a beloved figure among the city’s queer artists.

“This is someone who had the phone number of William Burroughs and Andy Warhol,” Preciado said.

Böttner also posed as a model for the photographers Joel-Peter Witkin and Robert Mapplethorpe, but she felt their images exploited her disability. This dehumanizing gaze is exactly what Böttner sought to invert and deconstruct in her self-portraiture, which celebrates her beauty and humanity.

“If medical discourse and modes of representation aim to desexualize and degender the impaired body, Lorenza’s performance work eroticized the trans-armless body, endowing it with sexual and political potency,” Preciado wrote in an exhibition text for the Documenta art fair in 2017, where she first showed her work.

The curator Stamatina Gregory, who brought “Requiem for the Norm” to the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in Manhattan in 2022, said the outpouring of support from Böttner’s past friends, lovers, colleagues and acquaintances was overwhelming. “I didn’t realize how significant hosting this show would be in broadening the research on Lorenza’s life and work,” Gregory said in an interview. “The period of her life that she spent in New York City was incredibly formative” in her studio experimentation and community building.

She even, Katz said, “loosened up as an artist, and began to use more color.”

In 1985, Böttner learned that she was H.I.V. positive. The physical derailment that came with the illness made traveling and working more difficult toward the end of her life, which she spent largely in Germany and Spain.

She died of AIDS-related complications on Jan. 13, 1994, in Munich. She was 34.

Preciado was introduced to Böttner’s work in 2008 while conducting research on the 1992 Paralympics in Barcelona, where Böttner served as the inspiration and became the physical embodiment of its armless mascot, known as Petra. Though he was eager to learn more about Böttner, he struggled to find any information beyond where she had received her education.

In 2015, when Preciado was named a curator of Documenta 14, which takes place in Kassel — where Böttner had studied art — it felt like divine intervention. “I am not a religious person and I don’t have any paranormal beliefs,” he said, “but something inside of me told me that I have to find Lorenza.”

Preciado tracked down Böttner’s mother and soon appeared on her doorstep. “Irene asked why I was searching for Lorenza,” he said. “I said, ‘Well, I am like Lorenza, I am trans.’ We hugged each other and she said, ‘I’ve been waiting for you for 20 years.’”

Her mother shared hundreds of Böttner’s artworks with him, as well as many personal effects that she had saved.

“I always believed in Lorenza’s art, and I knew that it was going to become popular,” Irene Böttner said in a phone interview. “I still believe it will gain more popularity.”

Preciado, who debuted “Requiem for the Norm” at La Virreina Center for the Image in Barcelona in 2018, said he found Böttner’s work to be “full of hope, transformation and emancipation.”

“It’s not work about trans or disabled people being victims of the system,” he said. “It’s a work of enormous political potency that has to be seen and given to the new generations.”

Overlooked No More

Since 1851, white men have made up a vast majority of New York Times obituaries. Now, we’re adding the stories of other remarkable people.

Renee Carroll: From the cloakroom at Sardi’s, she made her own mark on Broadway, hobnobbing with celebrity clients while safekeeping fedoras, bowlers, derbies and more.

Lizzie Magie: Magie’s creation, The Landlord’s Game, inspired the spinoff we know today: Monopoly. But credit for the idea long went to someone else.

Henrietta Leavitt: The portrait that emerged from her discovery, called Leavitt’s Law, showed that the universe was hundreds of times bigger than astronomers had imagined.

Miriam Solovieff: She led a successful career as a violinist despite coping with a horrific event: witnessing the killing of her mother and sister at the hands of her father at 18.

Beatrix Potter: She created one of the world’s best-known characters for children and fought to have the book published, but she never sought celebrity status.

Cordell Jackson: A pioneering record-label owner and engineer, she played guitar in a raw and unapologetically abrasive way.

Advertisement