Supported by

The French Think He's Good When He's Bad

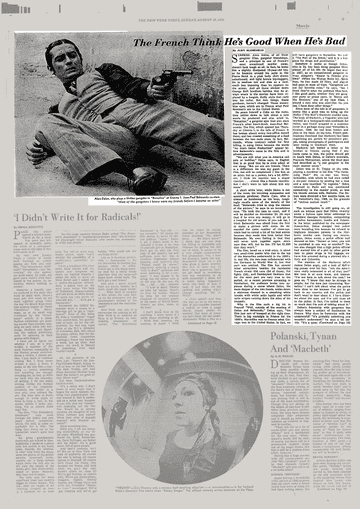

SURPRISE. Alain Delon, of all those gangster films, gangster friendships, and a principal in one of France's most sensational murder cases, doesn't look tough at all. In fact, he looks like a slightly dissipated 16‐year‐old boy as he bounces around his suite in the Pierre Hotel in a pink body shirt (twice unbuttoned) and tight brown hip‐huggers. He is medium tall and slim as a reed, much less imposing than he appears on the screen. And all those slicked down George Raft hoodlum hairdos that he al ways wears in the movies have been re placed by a longish, fluffy style that curls into his collar. But two things, thank goodness, haven't changed: Those watery blue eyes, which are to France what Paul Newman's are to the United States.

He pours himself a Coke on the rocks, then settles down to talk about a new movie he produced and also acted in, “Borsalino,” a gangster epic that also stars France's other heart‐throb, Jean‐Paul Bel mondo. The film, which opened last Thurs day at Cinema I, is the talk of France. It has broken almost every box‐office record there, and has created something of a feud between the two male stars. In fact, Bel mondo, whose contract called for first billing, is suing Delon because the words “An Alain Delon Production” appear be fore Belmondo's name in the film and in advertisements.

“We are still what you in America call pals or buddies,” Delon says, in English that is so good that he is even adept at our slang. “But we are not friends. There is a difference. He was my guest in the film, but still he complained. I like him as an actor, but as a person, he's a bit differ ent. I think his reaction was a stupid reaction… almost like a female reaction. But I don't want to talk about him any more.”

A short while later, while Delon is out of the room, his traveling companion and associate producer, Pierre Caro, who is almost as handsome as his boss, laugh ingly recalls more of the details of the feud. “Belmondo tried to stop the release of the picture,” he says in an incredulous tone. “He took the case to court, and it will be decided on November 23. He says that if he wins any money, it will go to a hospital for old actors. If you ask me, I think Belmondo was afraid from the first to make a picture with Alain. He de manded the same number of close‐ups. Alain had to cancel a lot of his best scenes because they made him look better than Belmondo. My own feeling is that they will never work together again. Alain says they will, but he lies. I'll bet $1,000 that they won't.”

The film, based on a true story, is about two small‐time punks who rise to the top of the Marseilles underworld in the 1930's. In real life, the two men collaborated with the Germans in World War II, but that part was omitted. The film has several other attractions besides the handsome French rivals: Old cars (34 of them), fist fights (35), and flamboyant fashions‐that for the most part are very true to the period. At a recent preview screening in Manhattan, the audience broke into ap plause during a scene where Delon, the more dapper of the two hoods, walks down a staircase dressed in a smashing white tuxedo with white satin lapels and white satin stripes running down the sides of the trousers.

Why is the film such a big hit in France? “Well, outside of the meeting of Delon and Belmondo,” Delon says, “the film just sort of bumped at the right time. There is big nostalgia in France for the 1930's. Marseilles was to France what Chi cago was to the United States. In fact, we still have gangsters in Marseilles. We call it ‘The Port of the Orient,’ and it is a key place for drugs and prostitution.”

Somehow it seems as though Delon, who is 34, has been doing gangster films almost all of his life. He began that way in 1957, as an inexperienced gangster in Yves Allegret's “Quand la Femme s'en Mole” (When the Woman Butts In). Since then, he has made 33 films, and played bad guys in most of them. “Gangsters are not my favorite roles,” he says, “but I think they're what the audience likes best. I like good parts, whether they are gang ster parts or priest parts. In ‘Rocco and His Brothers,’ one of my best films, I played a man who was saint‐like. So, you see, I have done other things.”

Since most of the talk is of gangsters, it seems like a good time to bring up the Stefan (“The Bull”) Markovic murder case. The body of Markovic, a Yugoslav who had worked as a bodyguard‐valet‐confidant for Delon, was found wrapped in a mattress cover in a garbage dump near Versailles in October, 1968. He had been beaten and shot in the head. At the time, French pub lications theorized that Markovic had been organizing sex parties for prominent peo ple, taking photographs of participants and later trying to blackmail them.

Markovic left behind a letter to his brother in Trieste, saying that if any harm came to him, the police should get in touch with Delon, or Delon's associate, Francois Marcantoni, whom the dead man had described as “a real gangster in the most sinister sense.”

Delon was in St. Tropez at the time, playing a murderer in the film “The Swim ming Pool.” His co star was Romy Schneider, with whom he had once ended a six‐year romance by sending her a rose and a note inscribed “Je regrette.” Delon returned to Paris and was questioned extensively in the murder probe, as was his blonde actress wife, Nathalie. The De Ions were divorced a few months later, on St. Valentine's Day, 1969, on the grciunds of “serious mutual insult.”

‘The investigation is still going on, at such an intense pace that Delon recently wrote a furious open letter addressed to President Georges Pompidou, complaining of police harassment, insults and threats. In the letter, published by the newspaper France‐Soir, Delon charged that police were hounding him because he refused to implicate innocent persons in the Mar kovic murder case. During one interro gation, Delon wrote, a police officer had shouted at him: “Sooner or later, you will be punished in one way or another!” De lon also charged that a high police official had warned him of a plot by other police men to plant drugs in his luggage, an, have him arrested during a planned trip t Italy and Colombia.

The mention of the Markovic affair makes Delon angry, and a look of suffer ing passes over his face. “Are the Ame‐i cans really interested in all of that, too?” His tone is at once tense, and intense. “I'm not here to talk about the case,” he goes on. “I know that may be strange to people, but I'm here just concerning ‘Bar salino.’ I can't talk about what the police have done to me because I've got to go back to my country and the police just don't want to hear about it. I have theor ies about the case, and I've told them all to the police. In fact, I've talked to them so much that I'm sick of talking about it.”

Delon's friendship with gangsters has always been a subject of fascination in France. Why does he fraternize with the underworld? “It's probably something you wouldn't understand,” he says a bit testilly. b”It's a ques tion of origin. I myself am Corsican, and in places like that they still have a sense of honor and the given word. That's something that is missing in 1970.” He says he is aware that gangsters are often involved in despicable things like drugs, prostitu tion, gambling, extortion and loan‐sharking. “I don't wor ry about what a friend does,” he explains. “Each one is responsible for his own act. It doesn't matter what he does. Most of them the gangsters I know… were my friends before I became an actor.”

I mention that some peo ple on this side of the At lantic have called him “the French Frank Sinatra” be cause of his associations with gangsters. He laughs. “I admire Sinatra,” he says. “That's all I can say about him. He probably under stands what I mean about origin and a sense of honor and the given word.” And as for Francois Marcantoni, a fellow Corsican and the alleged gangster mentioned in Markovic's letter to his brother, Delon says: “He will be my friend for life.”

Before the murder, the De lon lifestyle—one which thrived on the hedonistic pleasures of three‐star res taurants, swinging parties and the most beautiful women—was the subject of adulation by many French young people. That lifestyle seems to have changed dras tically. “I am not a drinker,” he says, sipping on his sec ond Coke, “and I am not a gambler—except with life, not cards. I can count the friends I have on the fingers of one hand. I'm not a dancer, and I'm not a night clubber, and I really don't like to go out. What I like to do is stay home with people I love. But if I do go out, don't like the fashionable places, because I am not po lite when I am out of my home. Most of the time I think it is very false to go around and kiss people and shake hands and say, ‘Hi, my

Delon is one of those peo ple who always seem to be getting into trouble. “It's probably destiny,” he says. He was born in Sceaux, out side of Paris, to parents who were divorced when he was a child. He had a rebellious adolescence, and was ex pelled from several of the Roman Catholic schools he attended, once for putting chalk in a teacher's ink pot. In his late teens, he worked for a while as a pork butcher with his stepfather, then en listed in the French marines and wound up in the bitter fighting in Indochina. He found the rigid marine dis cipline hard to. take, and in his first 12 months his head was shaved five times as punishment. He later spent three months in prison for borrowing a jeep that wound up at the bottom of a river.

Of the U.S. involvement in Vietnam today, he says: “I just think it's sad. It was hopeless when I was fighting there. In a way, I respect Nixon, because you don't know what kind of informa tion he has inside his room. I don't know if what he's doing is right or wrong. The only thing I'm sure of is that I'm just against war.”

Delon returned to Paris in 1955 without a sou in his pocket. To support himself, he worked as a salesman, a waiter, and a porter in Les Halles: where he was no ticed by some movie people, including actress Brigitte Au ber. In 1957, he accompanied some of his new friends to the Cannes Film Festival, Where he was spotted by Rock Hudson's agent, Henry Willson, who was then work ing as a talent scout for David 0. Selznick. A few days later Delon flew to Rome for a meeting with Selznick, who offered him a seven‐year contract, pro vided he learn English. De lon could not make up his mind. He returned to Paris and was introduced to di rector Yves Allegret, who persuaded him that it was better to be a big fish in a little pond than a small one in the turbulent waters of Hollywood. A few months later Delon made “Quand la Femme. s'en Mele” for Alle gret.

In his 13‐year career, De lon has worked with some of the greatest European direc tors, including Rene Clement (“Purple Noon”), Michelan gelo Antonioni (“Eclipse”) and Luchino Visconti (“Roc co and His Brothers,” “The Leopard”). He does not take time to think when asked to name his favorite. “Visconti, for his personal understand ing,” Delon says of the Ital ian director, who is a close friend.

John Garfield is the actor he idolizes most. “He did 10 years before what everybody did after.” He also admires Montgomery Clift, because he “never moved a muscle unnecessarily”—also a Delon trait.

Advertisement