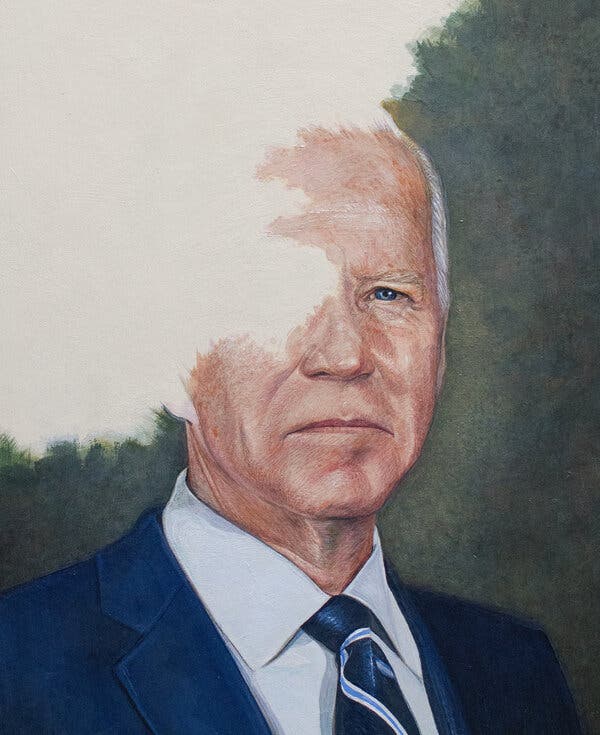

Joe Biden’s Interrupted Presidency

He sought the office nearly all his life. When he finally got there, it brought out his best — and eventually his worst.

Supported by

Robert Draper covers politics for The Times. He interviewed more than two dozen current and former Biden advisers; legislators; and Democratic colleagues and allies in Washington and Wilmington, Del.

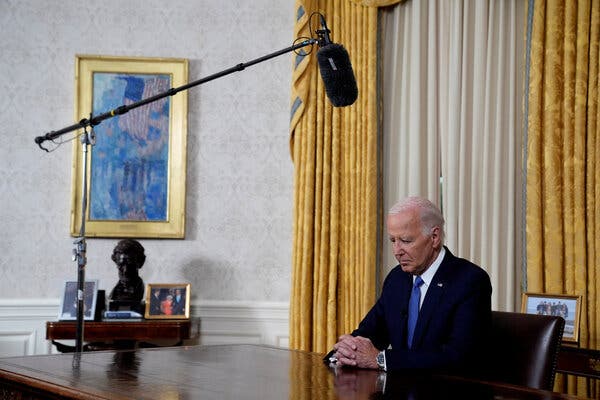

Shortly after the 11 minutes were over and President Joseph R. Biden Jr. arose from behind the Resolute Desk in the Oval Office on the evening of July 24, he and his family filed out to the Rose Garden.

Listen to this article, read by Robert Petkoff

A throng of White House staff members were waiting outside, under a slight drizzle, with a faint rainbow emerging overhead. Most of them spent the preceding hour nervously eating pizza in the East Room of the White House before growing hushed to listen to their 81-year-old boss speak to the nation. Several of them had been crying earlier in the day. But midway into his speech, Biden began to enumerate his administration’s considerable legislative achievements — among them, “And we finally beat Big Pharma,” a line he had fatefully mangled in the debate with Donald J. Trump less than a month earlier, abruptly dropping the hammer on his political future. As he proceeded through these shared highlights, the tenor in the East Room seemed to change, and a few of the staff members proudly shook hands and hugged one another.

Now Biden spoke only to them, through a microphone someone handed him (according to a video of the event that I obtained). “My name is Joe Biden, and I’m Jill Biden’s husband,” he began, grinning broadly at his familiar joke, as his wife stood beside him, noticeably more subdued, working through her own emotions. “Look,” he told his aides, “the only reason that we’ve had the progress that we’ve had is because of you. And that’s not hyperbole.” He added, in a raspy but otherwise even voice: “I’m so damned proud to be a part of you. I really mean that.”

Sounding anything but deflated, Biden exhorted his staff members to think about the work there was left to do over their final six months. He wanted to extend prescription-drug benefits. He wanted to force billionaires to pay their fair share in taxes. “We can start to help lay the groundwork for Kamala,” Biden said of his vice president and now heir apparent, who was already out on the campaign trail.

He wrapped up his three minutes of remarks with a stage-whispered call to arms, as if it were a secret plan: “Let’s elect Kamala!” After their ovation, the president urged his staff to get to work on the ice cream stationed behind them. Biden cracked a few other jokes but didn’t stay for dessert. Instead, the 46th president of the United States retreated with his wife down the walkway to the residence.

Tomorrow would be different. He would still be president, but in a manner that no predecessor had been previously subjected to, he would now serve as his party’s leader in ceremonial terms only, having been forcibly thrust to the margins of the national frame by other party leaders as all attention turned to the Democratic nominee that Biden believed should have been him. But at least for this moment, he seemed to speak and move with a younger man’s ease, somehow lighter than before, as if no longer burdened by his father’s admonition, Get back up! Biden had risen as high as any American could go, had fallen back to earth, had gotten back up one more time and now had relinquished the pursuit that had animated his entire political career.

It was as if the Joe Biden of the previous month — pugnacious, defensive, all but stricken blind by his own ambitions — had suddenly given way to an entirely different human being, one defined by selfless accommodation. But those two sides of the same man have always been present, and at times in conflict, throughout Biden’s 52 years in national political life, and the presidency brought out both sides of him: his best and, later, his worst. He reached the office by challenging Donald Trump in a campaign that he would come to call a fight for the soul of the nation; in doing so, he created for himself a kind of self-mythology in which his own fate was entwined with that of the country’s.

Everyone who becomes president has had a long personal relationship with the idea of the presidency. No one who gets there has not yearned for it for years, and it means something different for each. A Biden presidency, in his imagination, would let him transcend the humble origins he always proudly wore on his sleeve and then make good on his own redemption by widening that American dream to include others who had been left out of it. He would pass through unimaginable personal tragedies — the deaths of his first wife, Neilia, and his daughter Naomi just after he was elected to the Senate and then, when he was the vice president, the death of his oldest son, Beau — that would shape his public life.

But Biden, as the oldest chief executive to take office, took on the job having spent more time dreaming of it than any previous president. He reached the presidency with more governing expertise than any of his predecessors, but also well behind his own schedule, in a sense already running out of time. The flurry of activity that marked his administration was that of a man who had tried for literal decades to get there, accumulating plans and experiences along the way. He made his mistakes, especially in the chaotic troop withdrawal from Afghanistan and in failing to secure the Southern border, but even as Republicans denounced him as terminally enfeebled, he ushered in a wave of projects and reforms like no Democrat before him in more than a half-century.

And yet before it was even over, he had been deemed too old to win a second term and too old to finish it if he did win: the nation’s first too-old-to-be-president president. His decision to quit the race ended one of the most remarkable chapters in American political history and started one that may yet define his legacy. After all, that last chapter will not be written until after the election in November. Would Biden be the hero he always wanted to see himself as, the man who had, with grace and humility, stepped aside so Harris could seize the moment? Or would he become the spoiler who refused to face the stark reality of his own decline and held the Democratic Party hostage to his own ambitions — even as he insisted nothing less than democracy was at stake?

As he takes the stage on the first night of the Democratic National Convention, both outcomes remain possible. His legacy — once that of a skilled legislator who then became the able No. 2 man to the nation’s first Black president — is now tied to that of Kamala Harris, his vice president and understudy who has taken center stage. Should Harris win in November, becoming the first female president, Biden may best be remembered as a president who did not so much make history as facilitate it, twice over, and who also helped deny Trump’s two quests for a second term, first by beating him and then by stepping back so that a more able Democratic candidate could do the job. That Joe Biden could end up being, as he once put it, a human “bridge” to history marks a final plot twist in my reporting for this article, which began weeks before Biden’s career-ending debate and includes interviews with more than two dozen current and former Biden advisers, legislators and other Democratic allies. (The White House declined to make the president available to be interviewed.)

In the short weeks since what could be called Biden’s abdication, amid the swelling energy and excitement for his vice president — the rapturous rallies, the explosion of new voter registrations and the rising tide of polls and donations, even a “White Dudes for Harris” Zoom call — there had to be a sting for Biden, still the sitting president but now watching from the sidelines as she enjoyed an outpouring he never had. When Harris introduced Tim Walz as her running mate on Aug. 6 at a thunderous event in Philadelphia, neither of them mentioned Biden at all.

A self-described ‘Senate man’

Seemingly from the start of his Senate career, Biden’s sense of self was bedeviled by the specter of the presidency. He would always be, in his phrasing, “a Biden,” a desired elevation of his working-class family to nobility as another aspect of that self-mythology, but that Kennedyesque tableau needed the office to complete the picture. Though his natural habitat was arguably the Capitol, where Biden spent more than half his adult life, he never stopped seeing himself as a scrapper from Scranton, Pa., whom the elites looked down upon. Even after becoming one of the youngest candidates ever to be elected to the U.S. Senate, he bristled at the slightest insinuation that his calling might be seen as lowbrow, telling one crowd in May 1973: “Those of you who are doctors and lawyers and Indian chiefs in the audience, how can any of you possibly do as much good if you’re very good at what you do as I can do if I’m very good at what I can do? You can’t.”

In that same 1973 speech, Biden described his recent election as “achieving a life’s ambition to seek the highest elective office, with one exception, in the land.” That one exception always seemed just out of his reach. He was the chairman of Jimmy Carter’s campaign steering committee in 1976; he received mention as a potential running mate for Walter Mondale in 1984, the same year that a Times reporter wrote, “Senator Joseph R. Biden Jr. of Delaware makes little secret of his higher ambitions.” He declared his candidacy in June 1987, only to withdraw three months later amid revelations that he had plagiarized portions of his stump speech. He briefly considered running again in 2004; then he did so in 2008 and lost resoundingly in the primaries. He saw another chance eight years later from his perch as vice president but was discouraged from taking it by the party’s leader, President Barack Obama; he finally succeeded in 2020, though by now as a grandfatherly eminence rather than the Achilles-like protagonist he had once been seen as by the Washington elite.

“He is a person who in his personal and professional life has experienced both great highs and great lows,” Ron Klain, Biden’s former chief of staff and adviser for over 30 years, told me. “That kind of seasoning gave him a sort of levelheadedness that not many others could bring to the presidency. And his many years in the Senate taught him patience. We went through a phase in 2022 with the Inflation Reduction Act when talks were stalled, and we were said to be idiots because things were taking so long. And he said: ‘You know, this is the way the Senate works. It takes as long as it takes.’ ”

His long journey to the White House coincided with, and would ultimately challenge, the widely held axiom in contemporary American politics that governors are best suited to be presidents. Biden, by contrast, was a self-described “Senate man.” Sixteen presidents before him had served in the Senate, none for more than 12 years. Biden had represented Delaware in the upper legislative chamber for 36 years. He worked with seven presidents and dozens of foreign leaders.

He first achieved national distinction as the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, where he oversaw two of the most notorious Supreme Court confirmation hearings in recent memory. First, in 1987, he led the successful fight to defeat the nomination of Judge Robert H. Bork, a Reagan appointee whose views were deemed too extreme by Biden and others. Four years later, he presided over the hearings for Clarence Thomas’s embattled nomination to the Supreme Court, when Anita Hill accused the judge of sexual harassment. Biden’s willingness to indulge Republicans on the committee who sought to turn the hearing into a referendum of Hill’s character, and his decision not to call as witnesses more women who were ready to testify with claims similar to Hill’s, were widely criticized. At the start of his 2020 presidential campaign, knowing this painful history would be exhumed, Biden called Hill to express regret. She then publicly declined to call his words an apology and said she remained unconvinced he had taken responsibility.

In his leadership of the Foreign Relations Committee, he was on less contentious ground, with an understanding of geopolitics so expansive that early in 2004 he laid out in detail to Romania’s minister of foreign affairs, Mircea Geoana, how to make the case for why Americans should see strategic value in that country being admitted to NATO, which ultimately came to pass that year. He crossed paths with hundreds of fellow legislators, learning along the way to collaborate with those in Congress who did not share his state’s concerns. As his longtime friend and former Senate chief of staff Ted Kaufman put it to me, “All those committee hearings, all those relationships he’d developed in the Senate, are why he came into the White House with more knowledge than any other president in our history.”

According to those close to him, Biden believed he had become president in no small measure because of his senatorial impulse to build a winning coalition — in this case, with the progressive wing of his party that had felt disrespected by the Hillary Clinton campaign four years earlier. “When he became president, he felt compelled to govern with them being a part of it,” said Senator Chris Murphy, a Democrat from Connecticut who would become Biden’s point man in the Senate on gun legislation. “And Joe Biden’s a loyal guy.”

Murphy went on to say: “I also think Biden went through this metamorphosis. He went from being a neoliberal to being an economic nationalist. He came to the conclusion that the markets were fundamentally broken, that power was too concentrated and workers were disempowered. I don’t know when that happened, because he didn’t campaign that way.”

Later, I asked Kaufman, who had been with Biden since serving on his first Senate campaign in 1972 as an unpaid staff member, if his old friend had undergone some kind of political transformation in the White House. Kaufman politely replied that this was a crock. Senator Biden, he reminded me, had represented corporate-friendly Delaware, not Vermont. He hadn’t rolled up his double-digit electoral majorities every six years by waving a pitchfork. Rather, Biden had been mindful of all his constituents — not just unions and minorities, but also creditors who opposed bankruptcy reform and middle-class white voters who wanted more cops on the street. “That’s what he learned in the Senate, listening to what everyone’s got to say,” Kaufman told me. “It’s not ideological.”

That being said, Kaufman added, his friend felt an almost genetic connection to those who were disadvantaged and otherwise underestimated. Biden himself said as much during his first debate with Trump, in September 2020, when the subject turned to prejudice: People like Trump, he said (with a slight mangling of syntax), “look down their nose on people like Irish Catholics, like me, and grew up in Scranton.”

Bidens against the world

When I first met Biden in the fall of 2005, while on assignment to write a GQ magazine profile about him, he had already been a U.S. senator for 32 years, had been a presidential candidate once and was positioning himself for a second run. I imagined him as the quintessence of Washington establishment, a man on top of the world. It surprised me, then, when one day our conversation turned to the sitting president, George W. Bush. Biden proceeded to deconstruct Bush’s native privilege in a way that I, a biographer of the president, hadn’t considered: “And all you’ve got to do is look from the road in Kennebunkport at the estate, and you’ll understand. It’s not even that it’s nice. There’s nicer places. But it is a rock. It is a peninsula. It’s old money. Power. Establishment. There’s an understatement to it. But there’s an awesome rooted power to it.”

Biden made clear to me that he didn’t dislike the president. Still, he didn’t care much for the way Bush had blithely C-minused his way through Ivy League schools that many of lesser means would have killed to be able to attend. He didn’t like the way the president assigned pet names to those around him, telling me: “There’s a bullying aspect to that. If I give you a nickname, I’ve become your coach.” His critique of Bush struck me as acutely personal. Here was one of the most powerful politicians in America, devoting inordinate thought to what someone else had that he (and yes, others) didn’t. To my discredit, it didn’t seem terribly significant at the time.

As I would later realize, Biden was all but drawing me a diagram of his own deeply internalized class-consciousness. Without any prompting by me during our three months together in 2005, Biden would describe the indignities suffered by his father, Joe Sr., an elegantly dressed and soft-spoken man who never managed to make his mark in the world but who instilled in his progeny an abhorrence of self-pity. One such story he told me, which he later memorialized in his book “Promises to Keep,” recounted his father quitting his job at an auto dealership after a company Christmas party, when the owner showed his appreciation for his workers by pouring a bucketful of silver dollars onto the dance floor and watching with amusement as they scrambled to pick up the coins.

“That’s an abuse of power,” Biden told me back then. It was hard to disagree with him. Still, what did that mean to Joe Biden the legislator and aspiring president?

It meant, in his smaller moments, a jut-jawed and insular Bidens-against-the-world combativeness. It meant, in 1987, lashing out at a voter who seemed skeptical of his educational standing by saying, “I think I have a much higher I.Q. than you, I suspect.” It meant feeling the need to enumerate and embellish his achievements — “I’m the guy that did more for the Palestinian community than anybody,” he informed the podcaster Speedy Morman last month — or at times to invent distinctions altogether, as when he claimed that he had been the first in his family to go to college, and also to have once been arrested in South Africa while trying to meet with the anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela.

It meant trusting only the very loyal, his family above all, who had helped run his first campaigns and ever since had joined him in all manner of suffering. The self-mythology he had long engaged in, an attempt for the Bidens to have standing and meaning like that of other American dynastic political clans, would blind him to his brother and son’s own attempts to trade on that name. It meant abiding his son Hunter’s and his brother Jim’s questionable business practices, while continually saying that he was “proud” of his son even as Hunter falsely denied having a child out of wedlock and was found guilty of federal gun charges. Hunter took a well-paying seat on the board of Burisma, a Ukrainian energy company, during Biden’s vice presidency; recent reporting revealed that he requested State Department assistance with a potential business deal for the firm in Italy, though there is no evidence that his father was aware of his attempts. That the family had shared so much hardship seemed, in Biden’s eyes, to immunize them from charges of misconduct.

But the memory of being dispossessed would also inspire in Biden genuine moments of empathy that not only provided comfort to others but also shaped federal policy. He entered the Senate having just lost his wife and daughter to an automobile accident, and he left the vice presidency having just lost his son to cancer. His entire political life, including his presidency, would reflect a dual recognition of, but also a dual reaction to, opportunity and misfortune.

Tethering his destiny to Obama’s

I went to visit Biden in the White House one day in September 2012, on assignment to write an article about the man he then served as vice president. When the two men first came to know each other in 2005, Obama was one of the junior-most members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, of which Biden was the ranking member. Undeterred by the star power of Obama and two other Democrats, Hillary Clinton and John Edwards, Biden announced his presidential candidacy in January 2007, banking on his superior experience. I spoke briefly to him on the phone a year later, just before the Iowa caucus. When I asked him how he felt about his chances, he exclaimed, “Good, actually!” Then he came in fifth, with less than 1 percent of the vote, and dropped out that night.

The Obama campaign saw Biden as the white working-class answer to questions that swing voters in the Midwest might have about the young, inexperienced Black senator whose father was Kenyan. Biden was wary of the offer to be Obama’s running mate. He had been a Senate committee chairman for most of the previous two decades — the man with the gavel, not an underling dispatched to attend the funerals of foreign leaders, as had been the lot of previous vice presidents.

He accepted it only after making clear to the nominee that he wanted the same deal that Walter Mondale told Biden he had gotten from Jimmy Carter: not a narrow portfolio but rather an imprint on all major issues, and being the last person the president would talk to about a policy decision before making it. Upon taking the job, Biden dispatched Ted Kaufman to meet with scholars of the vice presidency so as to understand the office’s potential.

Being a heartbeat away from the presidency amounted to a hinge moment in Biden’s career — a critical next step, but also a fraught one that played to his native insecurities. As one of his top aides would later tell me, Biden immediately grasped a Beltway verity, which was that there was no such thing as a successful vice president in an unsuccessful presidency. Biden’s destiny was now tethered to Obama’s. He brought with him a highly professional staff, many of whom would later be elevated to Obama’s own senior White House team.

Obama and Biden entered office in the midst of a severe recession that threatened to metastasize into something far worse. It amounted to a daunting test for a new president of limited experience — and by extension, a test of Biden’s ability to assist Obama. For the new administration’s first initiative, the federal stimulus plan that was intended to stave off the recessionary effects of the market meltdown in 2008, the vice president helped secure the crucial three Republican votes from Senators Arlen Specter, Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins. “He was willing to do something Obama wasn’t always eager to do — which was to go to the Hill, work the members, have the dinners,” recalled Jim Messina, who served as the White House deputy chief of staff and later ran the 2012 campaign.

Whenever Obama was leaning toward making foreign-policy decisions against his vice president’s recommendation, Biden — who had gone 36 years without a boss — would buttonhole an Obama longtimer to ask: “Tell me why he’s doing this. Tell me what he’s thinking.” So determined was Biden to understand the president that within a few years, the White House would be dispatching the vice president to explain Obama’s thinking to reporters as a “source familiar.” That was why I was visiting the White House in September 2012.

What I feel comfortable saying about this encounter, given that it was not on the record, was that it was not materially different from the Joe Biden whom others came to know on Capitol Hill or on the Sunday talk shows — or even in his books. That Joe Biden could not resist reminding people of his proximity to the president and his influence over administration policy — or, in cases where he failed to persuade, emphasizing how he was ultimately on the right side of things. (At other times he pushed the president further than he wanted to go, as when Biden supported gay marriage in a 2012 interview, leading Obama to say that “he probably got out a little bit over his skis.”) I didn’t interpret his performance as an attempt to undermine Obama. Rather, it was in keeping with the long-held view in Washington of Joe Biden as an affable, skilled and knowledgeable yet notably self-conscious man forever seeking to convince people that he absolutely belonged in the upper climes of federal policymaking. His “I’m the guy who … ” verbal tic had become the most memorable protestation in town.

What was remarkable, then, was that the president would come to view Biden as his guy: the essential sausage-maker in the lofty Obama movement, wading into bureaucratic minutiae and mixing it up with legislators so that Obama didn’t have to; not to mention a man of heightened intuition, one who (according to one White House adviser) frequently urged the more deliberative Obama to “go with your gut.”

The vice president displayed those skills in what seemed at the time to be a losing cause: producing gun-safety legislation in the wake of the horrific mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School at the end of 2012. The bill’s Democratic co-sponsor, Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, was a folksy centrist who did not get along with the urbane, cerebral Obama and found in Biden his only real friend in the White House. The president had empowered Biden to lead the White House’s efforts on this issue, given his previous work in the Senate on the Brady Bill and the assault-weapons ban. But even before Manchin and his Republican co-sponsor, Pat Toomey, introduced their legislation, which would extend background checks to include gun-show and internet purchases, Biden recognized that the bill was doomed to fail in the Republican-controlled House. So the vice president and his staff drafted 23 executive actions, ranging from improving background-check data-sharing to enhancing gun-tracing efforts, that went into effect less than five weeks after the shooting.

But his more significant work would prove to be the relationship he formed with some of the grief-stricken parents of the 20 children who were slaughtered at the school. Days after the shooting, Biden called Mark and Jackie Barden, whose 7-year-old son Daniel was one of those killed. They talked for over an hour and a half. Early in the spring of 2013, when the Bardens and other Sandy Hook parents arrived on Capitol Hill for the first time to lobby Republican senators to vote for the bill, Biden cleared his calendar. Sitting with them for at least three hours, he did not mention legislative tactics. Instead, recalled Mark Barden, “He said: ‘Here’s what I’m telling you. Go home. You don’t have to do this. I’ve been down this road. I wanted to push through automobile safety. And in retrospect, I probably should have just been taking care of myself.’”

‘A way to defy the fates’

By Obama’s second term, he and Biden had become more than partners: They were friends. When the vice president confided to Obama that his eldest child, Beau, had been diagnosed with brain cancer and was struggling to pay for his treatment, the president offered to loan the Bidens money. A year later, in June 2015, the president gave the eulogy at Beau Biden’s funeral. Pledging to always be there for the grieving family, Obama then added what by then had become one of the more familiar signature lines in Washington: “My word as a Biden.”

Biden would memorialize these tender gestures in his 2017 book about his son, “Promise Me, Dad.” But the book also devoted considerable space to describing how Obama aggressively discouraged him from pursuing a 2016 presidential candidacy against Hillary Clinton, noting as well that certain Obama confederates “were putting a finger on the scale for Clinton.” As the president’s No. 2 — the one next in line to the Oval Office — Biden had reason to expect different treatment.

Since the very beginning of Obama’s second term in January 2013, the vice president had been discussing a candidacy with his team, according to one of them. Those discussions continued even after his son’s death. After watching an appearance on “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert” in September 2015 in which Biden acknowledged that he hadn’t given up on the idea of running, the actor George Clooney promptly called the adviser Steve Ricchetti and pledged to support Biden if he entered the race.

Two senior Obama administration officials would later insist to me that the president’s paramount concern in discouraging Biden’s candidacy was the emotional well-being of his devastated friend. But writing in his 2017 book, Biden didn’t seem to believe this. Obama, he could see, worried that a contentious primary battle between his vice president and his former secretary of state “would split the party and leave the Democratic nominee vulnerable in the general election.” Biden wrote, “This was about Barack’s legacy.” But the president seemed not to understand what a candidacy would mean to Biden and his family — and how devastating Obama’s discouraging words to his vice president were. As Biden wrote, “The mere possibility of a presidential campaign, which Beau wanted, gave us purpose and hope — a way to defy the fates.”

On Oct. 21, 2015, Biden stood in the Rose Garden, flanked by Obama and Jill Biden, and announced that he would not be running for president. A former aide would recall how the grieving vice president spent his last year in office seemingly drained of purpose, almost ghostlike.

Seven months after vacating the White House and becoming a private citizen for the first time in 46 years, Joe Biden watched TV footage of the white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va., and subsequently spoke on the phone to the mother of the young woman who was killed by one of the rally participants. Up to that point, the former vice president was laying the groundwork for serving on foundations and in university positions (including the Penn Biden Center) designed to maintain his relevance in both domestic and foreign affairs. Biden was “engaged” — his preferred euphemism, after Beau’s death, for keeping his political future in play. Charlottesville represented for Biden the threat to America brought on by the Trump presidency.

“And that’s when I decided that I, I, I, I, I’ve got to run,” Biden would say, according to the transcript of his October 2023 interview with Robert Hur, the special counsel who had been assigned by Attorney General Merrick Garland to investigate whether Biden broke federal laws by retaining classified documents from his time as vice president. That same interview, Hur would later assert in a bombshell report, revealed a president who came across as “a sympathetic, well-meaning elderly man with a poor memory.”

But Biden’s recollection of why and when he decided to run for president in 2017 remained indelible. So was his memory of 2015, when, he told Hur, in a moment that exposed the lasting hurt, “a lot of people” encouraged him to run for the Democratic nomination — “except the president.”

A leftward tilt

Four short years after leaving the White House, Biden returned to it, with the country in a state of upheaval. A pandemic had killed some 400,000 Americans. The month he took office, the national unemployment rate was 6.3 percent. Rioters at the U.S. Capitol had tried to overturn the 2020 election. Under President Trump, much of Obama’s legacy was eviscerated: the individual mandate that was the bedrock of the Affordable Care Act was removed, environmental regulations were rolled back, the federal judiciary (including the Supreme Court) was flooded with conservatives and the nuclear pact with Iran was discarded. Thirteen months into Biden’s presidency, Russia invaded Ukraine, a U.S. ally.

And yet the new president appeared to reintroduce himself to America as a living relic from a less troubled era, a 78-year-old anachronism not entirely aware of how much the country had changed: mentioning the word “unity” eight times in his Inaugural Address, continuing to embrace former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s 30-year-old characterization of America as “the indispensable nation” for which (as he said in his speech before Congress three months after taking office) “there is not a single thing, nothing, nothing beyond our capacity.”

His experiences with Republicans over the previous decade had been limited to high-level negotiations with leaders like Eric Cantor and Mitch McConnell, and before then, overseas trips with collegial senators like John McCain, Chuck Hagel and Lindsey Graham. He had no interlocutor inside the MAGA movement. His former legislative-affairs director, Louisa Terrell, said: “He knew the world had changed, and Biden showed a lot of interest in learning about his new colleagues on the Hill. He wanted data points about the new team that was in play, guys like Patrick McHenry and Garret Graves” — referring to two Republican House leaders who were hardly fans of the new president but were not seen as acolytes of the previous one.

So much did Biden prize bipartisanship that he announced a “unity agenda” in his first State of the Union address, consisting of seemingly unobjectionable items like cancer research, suicide prevention and mental-health programs for veterans. (Some Republicans objected anyway.) Preaching unity was, however, a matter of political necessity: Biden had only the barest congressional majority to work with in 2021. As it would turn out, many of Biden’s signature legislative accomplishments — infrastructure, gun safety, semiconductor manufacturing, aid to veterans exposed to burn pits and federal protections for same-sex couples — became law with bipartisan support.

“There was a presumption that the system was broken,” Biden’s White House counselor Steve Ricchetti told me. “And he demonstrated that it was wrong.” But this rosy assessment elides the fact that Republicans refused to engage on many key items of the Biden agenda even when those items hardly constituted an affront to conservative sensibilities, beyond the fact that it was a Democratic president who proposed them.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provided clean-energy investments that would overwhelmingly benefit so-called energy communities — meaning bastions of fossil-fuel production in places like Texas as well as former coal-mining sites and industrial brownfields in Republican strongholds.

Republican legislators unanimously opposed the I.R.A., as they had done with its antecedent, the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, which was intended to invigorate the pandemic-stricken economy. Its $1.9 trillion price tag fed into Republicans’ claims that Biden was promoting a “socialist agenda.” But much of the money would be delegated to states to spend according to their individual needs. “Early on, President Biden told me, ‘You know, a lot of these investments are going to go to red states, because a lot of those people are hurting,’” said Gov. Roy Cooper of North Carolina, a Democrat. In that spirit, Cooper told me, he directed $18 million in ARPA funding to revive an abandoned NASCAR racetrack in the town of Wilkesboro, situated in an economically struggling county that Trump carried in 2020 with 78 percent of the vote. That investment led to the North Wilkesboro Speedway hosting the 2023 NASCAR All Star Race, which in turn generated nearly $29 million in visitor spending benefiting Wilkes County.

Still, Republicans were not wrong in pointing out the strikingly leftward tilt of Biden’s agenda. His administration accomplished objectives that progressives had been pining for years to see realized, from forgiving student loans to expanding Title IX protections to include gender identity. He appointed more Black judges to the federal bench, 59, than any other single-term president in history and advanced the first Black woman to the Supreme Court.

Some of Biden’s progressive initiatives represented a continuation of longstanding policy preoccupations. But others seem to suggest a liberalized evolution in his thinking. The president pardoned minor marijuana offenders and others convicted of nonviolent drug offenses. Biden also announced his intentions to reclassify marijuana as a less dangerous drug. “These things aren’t in his comfort zone, obviously,” said Earl Blumenauer, a longtime proponent of cannabis decriminalization who was first elected to Congress in 1996, two years after Biden helped steer the crime bill (which included features like stiffer prison sentences that would later be seen as draconian) to passage. “But in my world, they’re huge.”

“For an older white man who most people would call a moderate, I certainly didn’t think he was going to be a progressive,” said Pramila Jayapal, the chairwoman of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. Jayapal, who would become a key figure in shaping Biden administration policy, told me that she had been advised early on by the liberal icon Bernie Sanders that “Biden is a very relationship-oriented person, and I think it would be good for you to get to know him.”

Sanders himself remembered how he and his wife, Jane, were warmly welcomed by the Bidens when he first got to the Senate in 2007, following 16 forgettable years as a disgruntled backbencher in the House. It was a case of Biden paying forward the kindnesses he himself received from elder senators who offered camaraderie when he first took office in 1973, weeks after the car accident that killed his wife and daughter.

Later, as a rival for the Democratic nomination in 2020, Sanders repaid the favor: He insisted that his campaign staff members treat Biden with civility. Biden came to see Sanders as the standard-bearer of a movement that would be necessary for his own success as a president. When Sanders visited the White House in early 2021, he told Biden that he would like to see a munificently funded social-spending bill — somewhere in the neighborhood of $5 trillion to $6 trillion. “Bernie,” he replied, “I want to go as big as we can possibly get.”

Ultimately, the multitrillion-dollar Build Back Better bill was downsized over a year to the $433 billion Inflation Reduction Act. That eventual triumph came to pass in no small measure because Biden understood the Senate’s meandering cadences better than a lesser-versed politician might have. But other feats of his presidency suggested a memory that stretched further back than his days in the Senate.

In December 2021, Biden flew on Air Force One to an event in Kansas City, where he would celebrate the recent passage of the infrastructure bill. With him on the plane was the representative of that district, Emanuel Cleaver. During their discussion, Cleaver said that he also hoped a portion of the money from the new legislation would deliver help to minority communities that had been damaged by past infrastructure projects. Biden replied that he knew exactly what Cleaver was talking about. Back in 1963, when Biden was a student at the University of Delaware, the Delaware Turnpike opened with great fanfare. “You know, when we built the freeway, we destroyed certain parts of the city and divided Black neighborhoods,” Cleaver recalled Biden saying. “We’ve got to start thinking about undoing that.”

In March 2024, a little over two years after their conversation, Cleaver received a notification from the Biden White House. The administration would be providing $3.3 billion “to reconnect communities that have been left behind and divided by transportation infrastructure.”

What then occurred to Cleaver said a lot to him about Joe Biden — including, he would tell me, why the president was so resistant to leaving office after only one term: “He’s had all these ideas over his career. And they’ve been piling up in his head, waiting for the opportunity. And then the opportunity finally hit, and he did not hesitate, and he wanted to keep going.”

Politics is in many ways a feat of memory: an unceasing recognition of where you come from, whom you answer to, what works, who can help, what is expected in return, why you ran for office to begin with. Notwithstanding the public lapses that would ultimately cause fellow Democrats to question his mental acuity and deny him a second term, the prodigious legislative skills derived from 52 years of accumulated knowledge continued to reside in America’s oldest-ever president.

Hours before Biden released his statement on the afternoon of Sunday, July 21, that he had decided not to seek a second term — having been effectively “pushed out” by Democratic leaders and donors, as his former chief of staff Ron Klain bitterly put it on social media — the president called the cellphone of his current chief of staff, Jeff Zients. As Zients would later tell me, Biden spent the first minute informing Zients of his decision. Then he told his chief of staff that their usual planning in 100-day blocks of time would now be reconfigured into a final 180-day flurry of activity.

“We have six months left,” Zients recalled Biden telling him. “And I want this six months to be as productive as every other six-month increment we’ve had.” That would involve concrete action, such as canceling more student debts and announcing price reductions that had been negotiated for 10 new prescription drugs. Biden also ticked off several goals, from reforming the Supreme Court to reinforcing the right to vote, that might not be attainable by the time he left office but that, as Zients put it to me, “would plant stakes in very important terrain.” Those stakes would help guide a Harris presidency and, in turn, shape Biden’s legacy.

A game of chicken with his own party

Almost from its inception, the Biden presidency unfolded in a kind of split-screen. One side of the screen featured an experienced legislator who knew how to get things done. The other side displayed the nation’s oldest president ever, aging before our very eyes. Biden entered office a few months older than the oldest to leave it, Ronald Reagan. In an increasingly visual era, with 90 percent of American adults owning a smartphone and 95 percent of them online, the president could not readily conceal his frailties from the public the way Franklin D. Roosevelt or John F. Kennedy once could. It might well have proved impossible for the White House to prepare the public for the optical experience of elder statesmanship. It might have been a tough sell to suggest that this version of Biden was superior to the younger, brasher candidate Biden circa 1987 — and to assert that a man who no longer walked or talked as he did even as a candidate in 2020 could still do his job, albeit as a man of diminished stamina.

In any event, the White House didn’t try. From the outset, Biden drastically limited his interactions with the media compared with previous presidents, while his 47-year-old press secretary, Karine Jean-Pierre, implausibly said of her boss in 2022, “I can’t even keep up with him.” A once-voluble ubiquity was receding from the media in inverse proportion to his advancing years, his “interviews” often limited to outlets that were unlikely to ask tough questions, including two conversations booked on Black radio stations following the debate in which the White House provided the hosts with suggested questions to choose from.

Even amid his administration’s string of legislative successes, Democrats privately shared their worries. Two Democratic legislators involved in the 2021 Build Back Better negotiations in the White House later told me that the president seemed at times to lose the conversational thread and at other times would lecture them like a cranky uncle, saying, “You were still in high school when I was doing this stuff in the Senate.” By the end of 2023, members of the diplomatic corps were privately sharing concerns with one former member of Congress with whom I spoke that the president’s memory appeared to be slipping in meetings with foreign leaders. Even without such information, 69 percent of Democrats polled last August believed that Biden was too old to serve a second term.

But the man who had assured supporters in 2020 that he would be a “bridge” or “transition” president now seemed unmoved by these concerns. One of his top advisers told me that he was unaware of any serious consideration given by Biden to forgo a second term. The president’s deeply loyal and deeply trusted inner circle, in the White House and on his campaign, recognized that a rematch with Trump would most likely be a photo finish at best but was now faced with the sobering reality that the incumbent could not campaign with the vigor he might easily have mustered in previous years. As his gait became less steady and his speech more halting and slurred, as the evidence mounted of his publicly confusing the names of world leaders and losing his train of thought, Republican adversaries escalated their attacks on the octogenarian president as being weak: weak in handling the porous border, weak in curbing inflation, weak in managing America’s response to conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza.

With the president’s approval ratings mired in the 30s, his supporters had one date to look forward to: June 27, the CNN debate against Trump, which offered the chance to showcase Biden’s mastery of details and overall humanity against a human fire hose of insults and untruths. He had done so in the past — even to heroic effect in 2012, when Vice President Biden’s performance against Mitt Romney’s running mate, Paul Ryan, effectively stopped the bleeding after Obama’s poor showing the week earlier. “All the panic on the Hill and among the grass roots went away once Biden left the debate stage,” Jim Messina told me, recalling that moment.

“If political campaigning is a decathlon, then debating is a sport that’s always been one of his strengths,” said David Plouffe, the Obama campaign guru and now the senior adviser of Harris’s campaign, who helped Biden prepare for his 2008 debate against Sarah Palin and his 2012 match against Paul Ryan.

Plouffe was among the allies who were stunned by Biden’s dismal performance — his inability to deliver boilerplate talking points and attack lines, his senior moment when he gasped out the non sequitur, “We finally beat Medicare” — all the more so because the campaign team had been confidently predicting victory to him and other Democrats all the way up to the day of the debate. We spoke five days after the debate, at which point the strategist likened the campaign’s state of play as the fourth quarter of a football game: “You’ve got to throw the ball on every play. Bus tours, 48 hours straight on the road, tons of interviews. It’s a comeback strategy — and by the way, it still might not work.”

But that sort of Hail Mary strategy could not happen now for the same reason it hadn’t happened before. Even as Biden was assuring his supporters that he had all the inner resources necessary to stage an improbable comeback, he was also complaining to them that his staff had overscheduled him, seeming to suggest that the key to victory was for him to work even fewer hours. If that seemed an untenable proposition to Democrats, Biden and his campaign were in essence saying: Too bad. The man known above all for his vast reservoir of empathy was now staging a game of chicken with his own party, daring them to either skitter out of his way or face a head-on collision at the Democratic convention. “I’m not going anywhere!” Biden now declared on the stump. And at his news conference following the NATO summit in early July, he responded to a question about calls for him to step aside by saying, “I think I’m the most qualified person to run for president” — a curious protestation by a president three years into his job, preceded seconds earlier by his misidentifying Harris as “Vice President Trump” (which the White House later corrected in its official transcript of the event).

On the morning of July 8, the president appeared on a Zoom conference call with hundreds of donors. Biden insisted that it was one bad night, that he’d been tired and ill, that things were going to be fine. The concerned viewers could clearly see him looking down throughout his monologue, as if reading from a script. A queue of questioners was growing. According to one listener, the first few questions selected by a Biden staff member were conspicuously softball, along the lines of “How can we help?” After the call, several donors complained to Biden allies that it had been a waste of their time.

Later that evening, Biden placed a call to the Congressional Black Caucus, who were among his most loyal supporters. The president listed his accomplishments and told them he intended to stay in the race. “I need you,” he told them. He did not take any questions.

To some, Biden’s refusal to step down was an all-too-familiar Washington story, one of power clung to at the risk of one’s own legacy, rationalized at the time by the belief in one’s own indispensability. Biden had seen more than his share of examples, from Supreme Court justices like William O. Douglas and Ruth Bader Ginsburg to former Senate colleagues like Strom Thurmond and Dianne Feinstein. “It’s a human story that repeats itself,” the Democratic political strategist James Carville told me. “Hell, the day after Bill Clinton got elected and everyone knew I wasn’t going into government with him, the phone just stopped ringing. I used to literally get the shakes, thinking nobody gave a crap about me anymore. That’s why the only way people leave Washington is in a pine box or in handcuffs. This power stuff is addictive.”

Some of Biden’s most ardent supporters began to express a new concern to me. The president seemed unlikely to beat Trump — that was bad enough. But to them, the genial, attentive man they knew now seemed beset by something worse than denial. He called in to “Morning Joe” on MSNBC to condemn “the elites in the party” for urging him to step down. He mocked the media for discounting him. He said the polls were wrong. To George Stephanopoulos of ABC, he protested, “How many people draw crowds like I did today?” He was angry at the world, and seemed to be shape-shifting into the man he had pledged to defeat.

But there was another key to understanding Biden’s intransigence, according to someone who has been close to him for decades. Here was a man whose son’s death had left him all but drowning in sorrow — a man whose book about his son contains the word “purpose” 25 times, including the subtitle (“A Year of Hope, Hardship and Purpose”). Leading the country was the purpose Beau Biden in his dying days implored his father to pursue; having done so, it was perhaps the one thing that kept Joe Biden from succumbing to grief’s riptide.

Parting paths with Harris

Watching as his own political future dwindled before his eyes, Biden at last shut the door on it — an act of humility, brought on by public humiliation. On Sunday, July 21, he made an unprecedented public statement, saying that he was standing down from his campaign. In doing so, he was admitting defeat, bowing to increasing public and private pressure after insisting for weeks that he would not give in.

But if the air was freighted with lament that day at Biden’s weekend retreat at Rehoboth Beach, Del., there was also something entirely different in the wind, unknown to all but a few. An hour and a half before posting his statement on social media, the president spoke on the phone with Prime Minister Robert Golob of Slovenia. For months, the Biden administration had been secretly working with seven countries on an elaborate prisoner swap that would result in the freedom of three Americans and one permanent U.S. resident who had been wrongfully detained in Russia for over a year.

According to a national-security source with extensive knowledge of the negotiations, Biden had been deeply involved with efforts to free the American prisoners. He had spoken with their families a total of seven times. He had taken numerous briefings, engaging himself on the subject across months of turbulence in which he also oversaw the American response to the Hamas attack on Israel and Israel’s crushing retaliation in Gaza, the continued effort to supply weapons to Ukraine, the conviction of his son on federal gun charges and the vicissitudes of his own political future.

One of the detainees, the Wall Street Journal correspondent Evan Gershkovich, had been sentenced in a Russian court on false charges of espionage to 16 years in prison two days before Biden’s call to Slovenia’s prime minister. What the public did not know was that the sentence was essentially a ruse: Two days before that, after extended negotiations, Russia had agreed to swap Gershkovich and the others for several imprisoned Russians, including two spies who were being held in Slovenia.

This was the reason for Biden’s call to Golob. Slovenia required that their prisoners being released in this international exchange first be issued a pardon by the Slovenian government. That fact had apparently not been conveyed to the proper authorities in that country, and the window to consummate the deal was rapidly closing. When the White House national-security adviser, Jake Sullivan, learned about this, he spoke with a Slovenian official, who agreed that a phone call from the American president to the Slovenian prime minister might instantly end the impasse. Biden’s call to Golob proved to be the final key that locked the prisoner-swap deal in place.

Over the next 10 days, the president would be briefed on the complicated logistics of Russia, Slovenia, Germany, Norway and Poland all preparing to transfer their prisoners to the exchange point in Turkey. Then came the late evening of Aug. 1, when the plane carrying the three Americans landed at Joint Base Andrews. Awaiting their arrival on the tarmac were their families, along with Biden and Harris. After Paul Whelan, who had been held for nearly six years, disembarked to cheers, it was Gershkovich’s turn. The first to embrace him at the bottom of the stairs was Harris, now the Democratic nominee.

Biden extended his hand. Gershkovich took it before throwing his arm around the president. Then the president pointed a finger to direct the reporter’s attention to his awaiting family, as if to acknowledge what mattered most. It was a moment for Biden to savor, a moment at the height of the presidency, of what he most believed it was for and could do: to bring to bear all the friendships and alliances across the globe in order to right a wrong. He had brought Harris inside those negotiations alongside him. And now, late at night, they parted paths. She went forward onto the campaign trail. And he went home.

Source photograph for artwork above by Kelia Anne MacCluskey.

Tanya Pérez and

Robert Draper is based in Washington and writes about domestic politics. He is the author of several books and has been a journalist for three decades. More about Robert Draper

Explore The New York Times Magazine

Inside a Rebel Stronghold: As Sudan’s civil war rages on, an elusive rebel army fighting for democracy has built its own state within a state — a vision of what the nation could become.

The Interview: Senator James Lankford discussed how political calculations killed his bipartisan immigration bill, the evangelical Christian vote and preparing for life after Donald Trump.

What’s New About the ‘New Right’?: Senator JD Vance and his allies represent a mind-set that dates back to Joe McCarthy and the dawn of the Cold War.

Silicon Valley’s Therapy Hack: In the Bay Area, therapists are embracing “coaching,” a new kind of practice in which they advise tech executives on becoming their best selves.

Deepfake Harassment: Sabrina Javellana was a rising star in Florida politics — until trolls used her face to make fake porn.

Advertisement