Supported by

The Next Stop for Denver Campus Protesters Is the Democratic Convention

Students in Denver behind one of the longest-running encampments in protest of the Israel-Hamas war disbanded the camp in May. They spent the rest of the summer planning for what comes next.

Audra D.S. Burch writes about race and identity and spent time in Denver, Colo., to report on the pro-Palestinian college encampment.

Three weeks into their pro-Palestinian encampment, student protesters gathered in the People’s Living Room, a communal space they had erected on a public college campus in Denver, Colo., to make a decision about the future of their movement.

By a show of hands, the student activists who had taken over the main quad voted to focus on the next big political moment: the Democratic National Convention.

As a physical symbol of resistance, the encampment, which began in late April, had lost its power. Thousands of students had left the campus, there had been a few violent brushes with the law, and homeless people moved in, changing the mission of the camp. On May 17, they decided to end the encampment, one of the longest running in the nation, and plot their next moves.

“The presidential election, in large part, is going to be a referendum on the genocide in Palestine,” said Paul Nelson, 25, a former Students for a Democratic Society chapter organizer and one of the encampment leaders, who will be at the convention. “We want to be within the sight and sound of the convention. We are going to be there to exercise our discontent.”

What unfolded tumultuously in the spring on college campuses turned into a far more quiet summer — but the organizing did not stop.

The Denver group was working to juggle their jobs and personal lives with pushing the movement along. They decided the way to keep up the momentum was through regular protests along with meetings and WhatsApp chats. So they demonstrated in front of the homes of two university regents weeks after the camp closure, drawing a stark condemnation resolution from the University of Colorado Board of Regents.

They also held a sit-in, marches and rallies throughout the city and organized a free screening of the movie, “Walkout.” On July 29, they held a rally in front of a local courthouse to demand all protest-related charges be dropped. There are about 80 cases.

The demonstrators see the escalations as necessary. Others, particularly some Jewish Americans, take the protests personally and see them as extreme and misguided — and even dangerous.

“When the encampment started, I thought it was great that people were standing up for what they believe in, speaking their minds and all that,” said Ellie Rapoport, 20, a senior at Metropolitan State University of Denver who is Jewish. “But once people started carrying around antisemitic signs and saying antisemitic things, it got a little out of hand, and it got a little scary to be on campus.”

For the student and non-student activists who once occupied a central space on the Auraria campus for weeks, the encampment tactic was part of nationwide protests against the Israel-Hamas war and U.S. aid to Israel. Like other young protesters across the country, they are calling for an immediate cease-fire and for universities to cut ties with Israel.

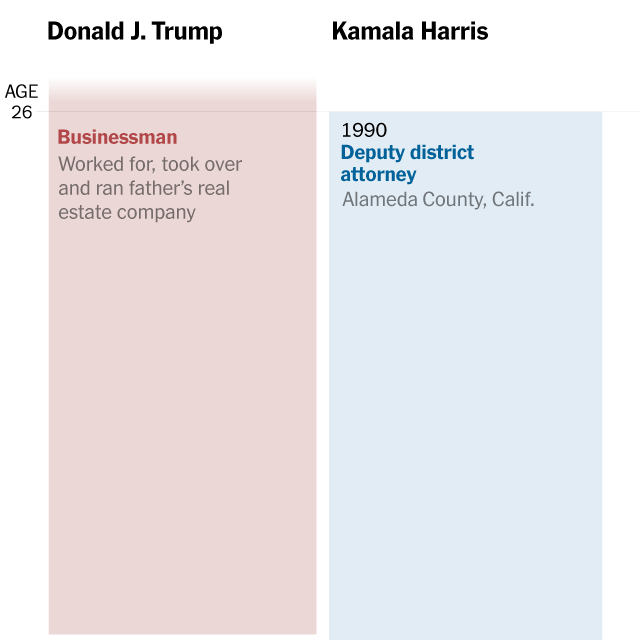

But the Denver activists also see a need to strongly denounce Vice President Kamala Harris, along with American foreign policies at the convention. Ms. Harris has expressed sympathy for Gazans and distress over the Palestinian death toll and issued forceful condemnations of Israel’s tactics. But, so far, she has not distinguished her stance on the war from that of President Biden, who firmly supported Israel but called for a permanent cease-fire at the end of May.

Ms. Harris’s national security adviser, Phil Gordon, said last week on social media that the vice president does not support an arms embargo on Israel. “She will always ensure Israel is able to defend itself against Iran and Iran-backed terrorist groups, adding “She will continue to work to protect civilians in Gaza and to uphold international humanitarian law.”

For the protesters, that is not enough. Many of them said they would remain uncommitted until they learn more about Ms. Harris’s response to the war if elected.

“Harris has been by the side of Biden as he has continuously given aid to Israel and shipped weapons to Israel, so we are going to march on her to stand with Palestine,” said Khalid Hamu, 22, who attends the University of Colorado Denver.

National pro-Palestinian leaders are promising tens of thousands of protesters will converge on the city — where Ms. Harris is expected to accept the presidential nomination amid deepening antiwar sentiments.

In Denver, a Democratic city, the protesters were mostly students who attend the University of Colorado Denver, MSU Denver and the Community College of Denver, all on the Auraria Campus downtown.

Collectively, they were one of the few encampments led by commuter students, who tend to skew older and hold off-campus jobs and, in some cases, are first-generation students. They were inspired by the Columbia University students who erected the nation’s most high-profile encampment in support of Palestinians.

With most every unflinching war dispatch, the demonstrations spread, growing in size and intensity — and arrests increased, too. Within a week, pro-Palestinian protesters had set up more than 100 camps across the nation.

After the SDS national branch on April 23 formally called for its local chapters to erect encampments in support of Palestine, the core group led by Mr. Hamu, Mr. Nelson and Harriet Falconetti, a 20-year-old college newspaper journalist — voted to start the Auraria Encampment for Palestine.

What began as a small collection of tents grew to some 70 brightly colored shelters housing hundreds of protesters. From the beginning, the activists leaned into visually dramatic ways to call attention to the growing death toll. At one point, they planted 10,000 miniature white flags in the ground to commemorate the deaths of Palestinian children killed in the conflict.

Daniel Bennett, executive director of Hillel of Colorado, a Jewish student life organization, said his group heard from about 30 students who were worried about the presence of the encampment. “Our students were not cowering in the corner, but they were very wary of the demonstrations,” he said. “We had students saying they no longer wanted to wear their yarmulkes.”

Soon, the protests, like on other campuses, began to transcend the conflict in Palestine and morph into something bigger: a rallying cry for police accountability, trans rights and a push for more universal civil liberties. They were supported by donations from individuals, businesses and a GoFundMe that generated about $5,000.

The closure of the encampment, which campus administrators called an “unauthorized occupation,” was for protesters the movement’s second act. They considered it a partial victory with MSU Denver agreeing to release publicly available financial information to the protesters, “as part of an open and ongoing dialogue.”

But other goals were not met. They did not win the three universities’ commitment to end investments and amnesty for the dozens of protesters who were arrested. They saw the summer as a time to regroup, reassess strategies and consider ways to apply more pressure in the fall.

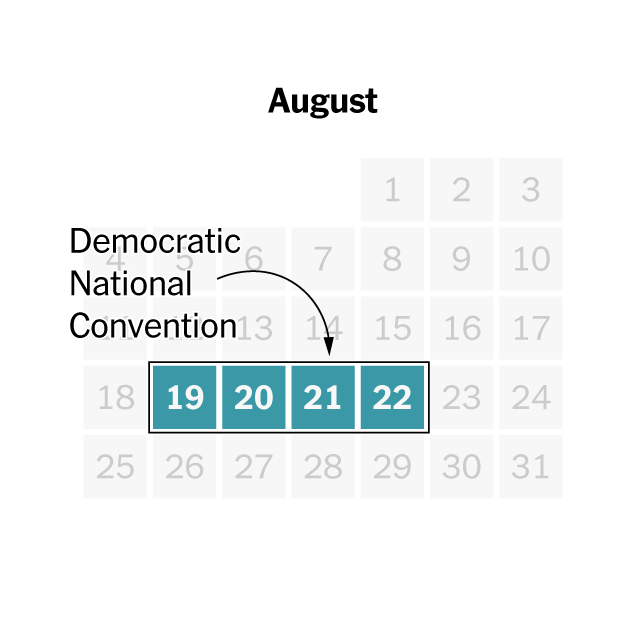

In July, they marched in Milwaukee at the Republican National Convention and about a dozen Denver activists will fly to Chicago to join the national Students for Democratic Society chapter at two demonstrations at the Democratic convention, big moments that they hope will generate enough energy to carry the movement into the new school year.

Faced with an ever-growing encampment that had already disrupted campus activities — and felt threatening to some Jewish students — Janine Davidson, president of MSU Denver, said administrators at the three colleges were trying to navigate fault lines.

“This was a national movement, and I was thinking ours would take a similar arc,” said Ms. Davidson, who has led Colorado’s third-largest public university since 2017. Her priority, she said, was trying to figure out, “how we can balance our value set about freedom of speech and education with safety and mission.”

In the months after the encampment shut down, Students for a Democratic Society, a national leftist youth organization influenced by Marxist and antiwar ideals, was barred from campus, and several students were suspended from their universities. Some are facing court dates resulting from protest-related arrests. Mr. Hamu and Mr. Nelson were arrested during the protests.

Protesters say that some students and members of the public accused them of making Jewish students feel unsafe, called them frauds who had waded into a war they didn’t fully understand and of being antisemitic — a charge the group denied. Mr. Hamu said that accusations of antisemitism muddled complicated issues.

Ms. Rapoport, the MSU Denver student, said she supported the encampment’s right to protest until it felt hateful toward Jewish students.

She said she even saw a protester carrying a sign that said “What Hitler did was right.”

Mr. Hamu said he was not aware of the sign.

Ms. Rapoport said she went to a listening session with the protesters and felt she was treated with respect. “Everyone had their space to talk, and we talked about our issues.”

An earlier version of this article misstated what was known about a protester carrying a sign that said, “What Hitler did was right.” Khalid Hamu, one of the protest leaders, said he was not aware of the sign. He did not say that he was made aware of it.

How we handle corrections

Audra D. S. Burch is a national reporter, based in South Florida and Atlanta, writing about race and identity around the country. More about Audra D. S. Burch

Advertisement