Supported by

What Minnesota’s Law on Free Tampons in Public Schools Actually Does

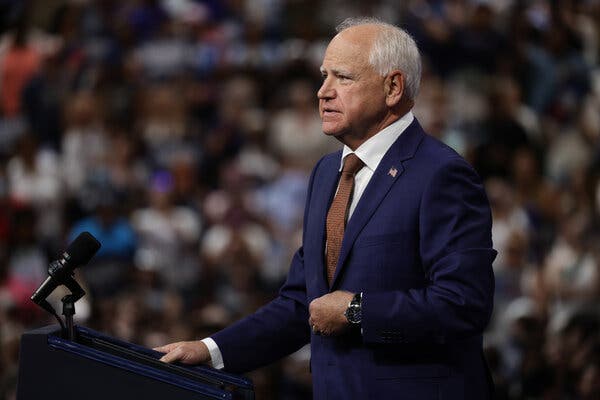

Conservatives have criticized Gov. Tim Walz over the law, but schools have not taken it as a mandate to put menstrual products into boys’ restrooms.

Emily Cochrane interviewed more than 20 former and current students, school staff, and lawmakers in Minnesota, as well as organizations that distribute menstrual products.

Tucked into a stack of budget bills Gov. Tim Walz of Minnesota signed into law last May was a measure that went largely unnoticed: Public schools would be required to provide free menstrual products to all students who needed them, beginning in the fourth grade.

The measure was spearheaded by teenagers like Elif Ozturk, who had listened to classmates in the restroom fret over not having a tampon, and Maarit Mattson, who began carrying extra pads in middle school, as a gesture of support for friends uncomfortable confiding in their parents about the start of their periods.

“It isn’t part of a political agenda,” Ms. Mattson, 15, said. “It was to make students feel safe.”

The new law took effect on Jan. 1 this year, with little sign of public opposition, and Minnesota joined about half of all states in passing legislation to improve access to menstrual products in public schools.

But when Vice President Kamala Harris named Mr. Walz as her running mate for the presidency this month, conservative commentators seized on one phrase in Minnesota’s law, which guarantees access to the products for “all menstruating students.”

Labeling Mr. Walz “Tampon Tim,” opponents including former President Donald J. Trump have accused the governor of a heavy-handed campaign to place tampons and pads in boys’ restrooms for transgender students, tying it to a broader conservative backlash over Mr. Walz’s support for L.G.B.T.Q. rights.

“Her running mate approved — signed into legislation — tampons in boys’ bathrooms, OK,” Mr. Trump, the Republican presidential nominee, said of Ms. Harris on Monday during a live audio stream on X. “Now that’s all I have to hear.”

The law was written by Democratic lawmakers with the intent of including transgender students, and has been celebrated by supporters for urging schools to put the products wherever they may be needed.

But with each of Minnesota’s more than 300 school districts responsible for drafting a plan for meeting the requirements of the law, schools have not interpreted it as a mandate to specifically place tampons and pads in restrooms designated only for boys.

In calls and emails to district officials across the state this week, none of the half dozen who responded said that their schools had placed menstrual products in boys’ restrooms.

Lawmakers in both parties, as well as some students, teachers and administrators, said that to their knowledge the products had typically been placed in girls’ restrooms or gender-neutral restrooms, as well as in places like the nurse’s office. Many schools already had a policy in place.

A spokeswoman for the Minnesota Department of Education said there was no requirement for the department to track plans developed by districts, and did not address further questions about the policy.

Reached in the final days of summer vacation, several Minnesota students, teachers and lawmakers expressed a mix of confusion and exasperation over the politicization of the policy.

“I think it’s kind of silly,” said Ms. Ozturk, now 18 and preparing for her freshman year at Columbia University. “This is necessary for us.”

Shannon McCarthy, a seventh-grade teacher who keeps a stash of pencils, Band-Aids, snacks and products in her classroom, said, “We are really trying to do our best for kids and getting kids whatever they need when they need it.”

Lauren Hitt, a spokeswoman for the Harris campaign, said that Minnesota’s law was “a bipartisan, common-sense policy to provide women and girls with basic health care products.” The criticism from Republicans showed how “extreme and out-of-touch they are on reproductive health care,” she added.

And it is not among the educational policies that Mr. Walz and his allies have highlighted during his tenure or on the campaign trail.

Menstrual products have been growing more expensive. A package of pads or liners costs about $6.74 over the past year, up 4.8 percent from a year earlier, while a package of tampons costs about $8.50, up 1 percent, according to Circana, a market research firm. Both products have seen rapid inflation in recent years, particularly in 2022.

Research shows that the costs can be a financial burden: Some teenagers have described missing class or using ineffective substitutes, as well as being embarrassed over not being able to afford the products.

“This is a dignity issue,” said Eva Marie Carney, the founder and executive director of The Kwek Society, which focuses on making period products available for Indigenous communities. “This is flipping the script on period shame, and having what one needs at school is critical to feeling good about having a period.”

More than half of the country’s state legislatures, along with Washington, D.C., have approved a variation of a law aimed at improving access to menstrual products in public schools. Some laws, like the ones in Alabama, Missouri and Nebraska, offer funding for such programs, without mandating that the products be available to all students.

In Minnesota, the drive for the new law came from several students in different districts, some of whom had successfully pushed for the policy in their own schools.

State Representative Sandra Feist, a Democrat, took up the legislation and pushed to make sure it covered all students who might need the products, regardless of gender identity.

“We just knew we wanted to draft it in a way that reached all of the students who needed these products,” Ms. Feist said.

One Republican, State Representative Dean Urdahl, a former history teacher, proposed an amendment mandating that the products be placed only in girls’ restrooms, thinking mainly of the maturity of younger boys.

“They’re not going to take it seriously, they’re going to flush them down the toilets and do other kinds of mischief,” Mr. Urdahl said in an interview. He added, “I didn’t want to hinder the accessibility.”

(At least one principal said that questions about maturity were a reason for the school’s not placing the products in boys’ restrooms.)

Other Republicans, including State Representative Patricia Mueller, raised concerns about the cost and another mandate on public schools.

“If we wanted to talk about period poverty, then you target where it’s mostly in need, which is for our female students in high poverty areas,” Ms. Mueller, a former full-time teacher, said.

Lawmakers ultimately settled on language that said “the products must be available to all menstruating students in restrooms regularly used by students in grades 4 to 12 according to a plan developed by the school district.” The overall education policy package passed through the Democratic-controlled legislature with some bipartisan support.

Some school staff and lawmakers said that attention now should be on other issues: mental health issues for students, a staffing shortage that has left schools to share a single nurse and the challenges of new testing and educational mandates.

“I want menstruating students to have access to menstrual products, and again, let the districts decide the best way to do that,” said State Representative Peggy Bennett, a former elementary schoolteacher and the top Republican on the education policy committee.

“You need to be able to read and write well to succeed in this state and nation, so I want districts to be able to focus on that,” she said.

Flynn Gray, now 20, wrote in a graduation speech about how important it was for there to be menstrual products in the girls’ restroom his senior year, a change championed by his female classmates. Putting them in the boys’ restroom, he said, would be an important next step.

Mr. Gray, who began to transition in his junior year of school, recalled the occasional quick handoff of a pad outside the restroom with a friend if he needed it, an interruption that drew uncomfortable attention to a personal need.

“You don’t realize how necessary it is until it’s not there for you,” he said.

Ernesto Londoño, Jeanna Smialek, and Christina Morales contributed reporting. Kitty Bennett contributed research.

Emily Cochrane is a national reporter for The Times covering the American South, based in Nashville. More about Emily Cochrane

Advertisement