Supported by

Big CITY

When Breaking the Dress Code Depends on Skin Color, and If You’re Skinny

A new City Council law seeks to pressure schools to undo bias in enforcing a dress code across the nation’s largest school system.

Ginia Bellafante writes the Big City column, a weekly commentary on the politics, culture and life of New York City.

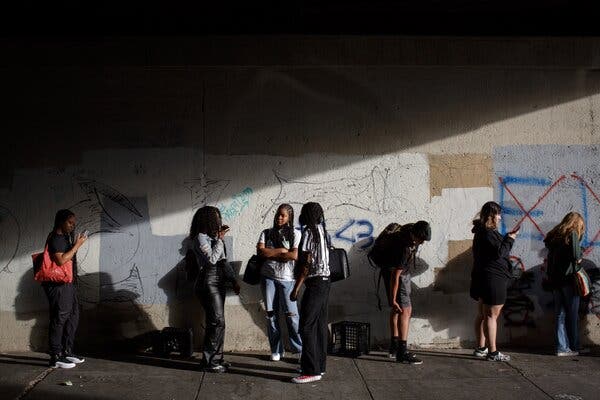

In June, a group of current and former New York City public school students arrived at a City Council hearing to speak out on the indignities of getting “dress-coded.” The term had evolved to refer to running afoul of apparatchiks who did not like what you were wearing, although rules about what counted as problematic were not always obvious, and enforcement of them could seem random and riddled with bias.

Accompanying the girls was an educator named Alaina Daniels, who introduced herself as a “white, queer, neurodivergent, nonbinary trans woman” with 12 years of experience teaching everything from robotics to activism. She had also worked as a “lunch lady” and an adviser to eighth graders. In that capacity, she explained to the Council’s Education Committee, she saw “marginalized students and teachers being policed by dress codes in ways that privileged communities are not judged.” Black, brown, queer and “fat” students, she said, were often upset because they had been punished for wearing tank tops or cropped tops, while their “skinny, white, cis peers” were left alone.

On too many occasions, children were made to feel as if they had the “wrong” body. Consequences of being dress-coded could range from a forced change into a grubby, oversize school T-shirt to being pulled out of class to maybe even missing the prom. In a written testimony, one student talked about getting dress-coded so many times that she was left needlessly anxious, adding that the disciplinary response seemed “to depend on the enforcing teacher or staff member’s mood that day.” Another student pointed out that she had seen a boy get reprimanded only once: when he took off his shirt in the lunchroom.

The group had shown up to support proposed legislation that would both require schools to make their clothing policies clear to students and parents — posting the rules on their websites — and, more meaningfully, to collect data on dress-code violations and penalties, broken down by month, week, student race and gender. The Council, which passed the law in July, is not empowered to mandate a universal dress code, but it could compel teachers and administrators toward greater self-scrutiny and accountability.

The legislation came with the committed backing of Althea Stevens, a councilwoman from the Bronx who, as a high school student in the late ’90s, organized her first protest, against a ban on skirts worn above the knee. As an adult, she still felt continually surveilled for her appearance, she told me, having been criticized for changing her hair while she campaigned — a change, she said, that was prompted by emerging bald spots that had developed from the stress of running for office. She sponsored a companion resolution, which also passed, calling on the city’s Department of Education to develop a dress-code policy that would account for various expressions of cultural, gender and body difference.

Three years ago, the department updated its dress-code guidelines largely with this in mind. In August 2021, a federal appeals court had ruled that under Title IX, school dress codes could not discriminate on the basis of sex. This followed from a lawsuit brought by girls at a North Carolina charter school who challenged an order forbidding them to wear pants or shorts. In New York, the specifics of dress-code policy are left to the discretion of individual schools, but they “must be gender-neutral and applied uniformly” and must consider “evolving generational, cultural, social and identity norms.” Still, the guidelines leave enough room for interpretation, stipulating that students have the right to wear what they like except when it “interferes with the teaching and learning process.”

But whose focus and concentration are at issue? Next month, Girls for Gender Equity, a Brooklyn nonprofit organization, will release a report on dress codes in schools — its third over the past four years. One of the themes that emerged from speaking with young women, Quadira Coles, the organization’s policy director, told me, was that certain kinds of clothing left students feeling leered at more by teachers — both male and female — than by their classmates, even though teachers often cited one stylistic choice or another as distracting to other students.

One way to circumvent this sort of problem would be for the city to require all students to wear uniforms, as most charter schools do. In the late 1980s, Mayor Ed Koch gave serious thought to this idea. A pilot program was implemented, but it did not take off. During his second presidential run, Bill Clinton sought to encourage school districts across the country to adopt uniforms, only to be accused by Republicans of another effort at government intrusion.

Still, the way that material inequities were playing out at schools in the ’90s — often leading to violence over who had what expensive pair of sneakers or sunglasses and who did not, for example — drove a broad enthusiasm for what sociologists called “noncompetitive dressing.” In 2000, Philadelphia became the first major American city to insist on uniforms for all students in its system. Two and a half decades later, it remains the only one.

In addition to the challenges that would come with any attempt at incorporating uniforms across the biggest and most diverse school system in the country are the identitarian ideologies that are now much more central than they were 30 years ago. Self-expression is paramount and is its own pedagogy.

Recently, I spoke with Jasmina Salimova, a June graduate of a high school in Staten Island, who appeared at the council hearing. She had watched dress-coded friends be humiliated and lose confidence, she told me. During the pandemic, she had played around with the way that she wore her hair and dressed, and she found it liberating, transformative. From that vantage, she learned more about the intersection of fashion, art, culture and oppression. This led her to activism, to marching in Albany, to making the decision to take a gap year rather than go straight to college to study computer science as her parents had expected. All of this convinced her that when you limit how people look and dress, “you limit innovation.”

But not all forms of self-expression lead there. Talking about the research at Girls for Gender Equity, Ms. Coles said that students were put off when teachers complained about viral social-media moments that led to the wide-scale purchase of the same item, say a new purse. This would evolve into a kind of distracting frenzy that, in the teachers’ view, had to be addressed as a dress-code violation. “What young people reported is that they were afraid to play around with trends,” Ms. Coles said. The system allows for teenagers, who have always maintained an ambivalent relationship to conformity, to have a say in evolving dress codes. Presumably so will TikTok.

Ginia Bellafante has served as a reporter, critic and, since 2011, as the Big City columnist. She began her career at The Times as a fashion critic, and has also been a television critic. She previously worked at Time magazine. More about Ginia Bellafante

Advertisement