Protesters Will Converge on Chicago. City Leaders Say They’re Prepared.

Activists plan to push for policy changes on Gaza as Democrats hold their convention. Chicago officials are confident they will avoid a repeat of the chaos that unfolded in 1968.

Supported by

Mitch Smith and Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs

Mitch Smith reported from Chicago. Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs reported from New York.

As delegates arrive in Chicago on Sunday ahead of the Democratic National Convention, protesters plan to march along Michigan Avenue. On Monday, as the political show begins inside the United Center, demonstrators say they will gather by the thousands outside. And as the convention goes on, activists say, so too will the protests, every single day, showcasing divisions on the left during a week when Vice President Kamala Harris is trying to project Democratic unity and enthusiasm.

From the moment the Democrats chose Chicago as the site for their nominating convention, it was a foregone conclusion that protesters would show up in large numbers. The city has a long tradition of left-wing activism, and nominating conventions tend to attract demonstrations.

But as the war in Gaza left tens of thousands dead and divided the Democratic Party, expectations for large protests heightened, as did the memories of protests devolving into clashes with the Chicago police outside the party’s 1968 convention.

City officials have argued in recent days with activist groups over protest details, including the length of a march route and whether a sound system will be allowed. Still, the city, long led and dominated by Democrats, has sought to convey an openness to the demonstrations and confidence that everything will go smoothly.

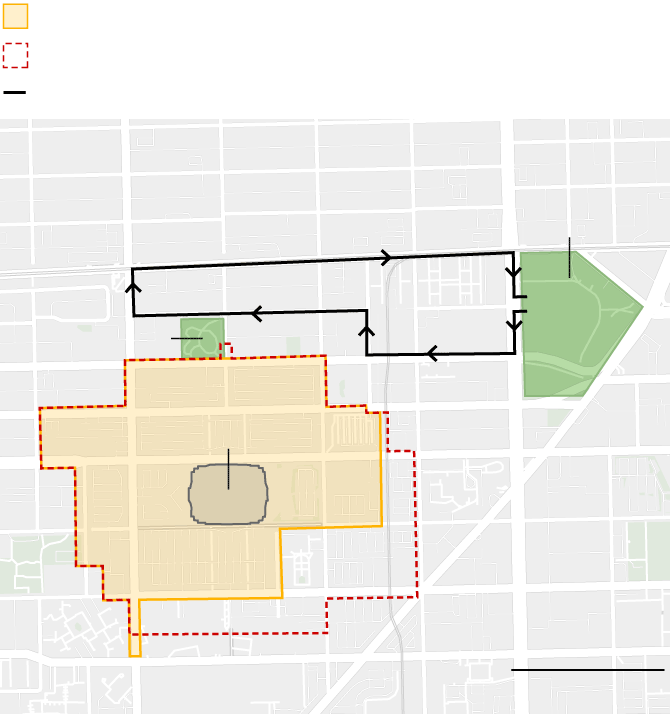

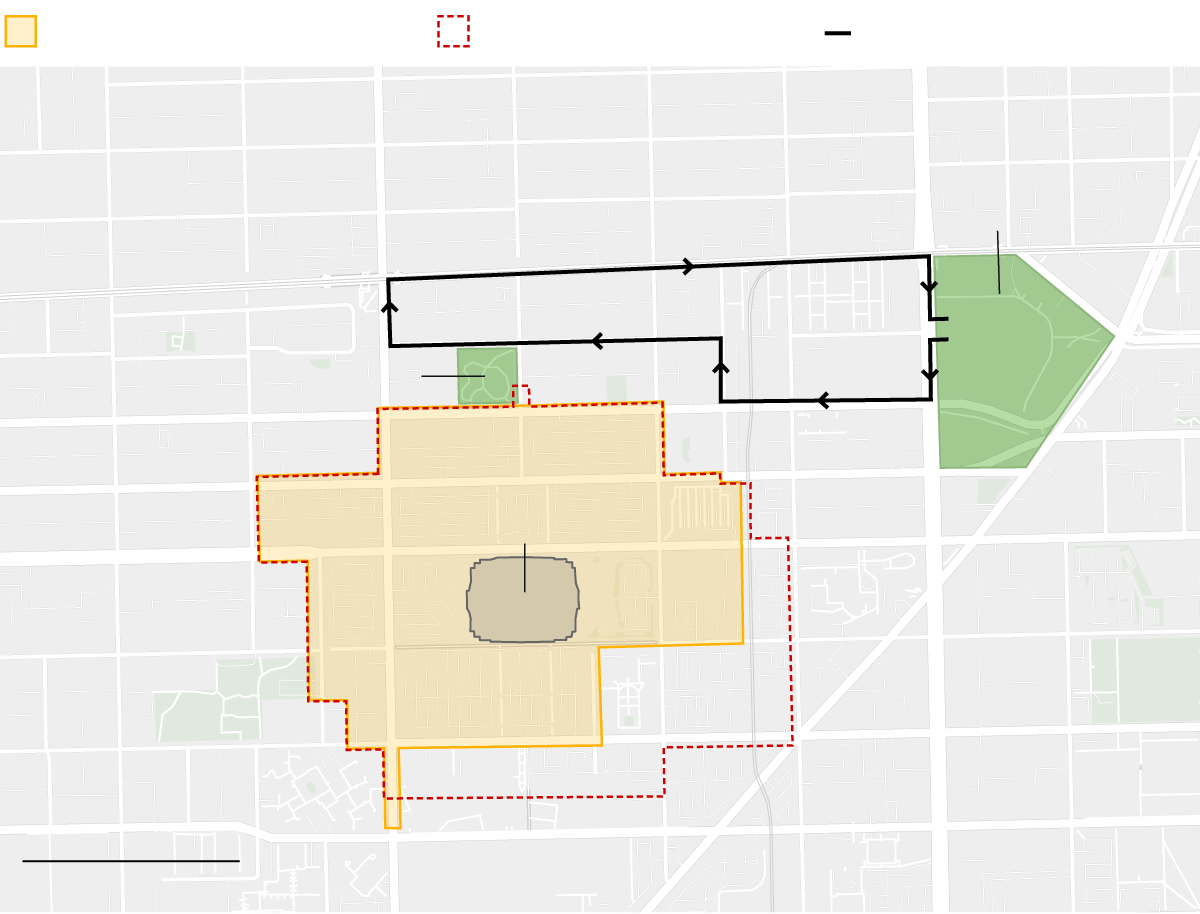

Security Perimeters and Chicago’s Proposed Route for the Coalition to March on the D.N.C.

Pedestrian restricted perimeter

Vehicle screening perimeter

City’s proposed march route

N. Damen Ave.

CHICAGO

Union Park

W. Lake St.

Park #578

W. Washington Blvd.

N. Hoyne Ave.

United Center

W. Madison Ave

S. Paulina St.

N. Ashland Ave.

W. Adams St.

W. Jackson Blvd.

Pedestrian restricted perimeter

Vehicle screening perimeter

City’s proposed march route

CHICAGO

N. Damen Ave.

Union Park

W. Lake St.

Park #578

W. Washington Blvd.

N. Ashland Ave.

N. Hoyne Ave.

N. Leavitt St.

United Center

W. Madison Ave.

S. Paulina St.

W. Adams St.

W. Jackson Blvd.

“It has to be safe and peaceful and vibrant and energetic,” said Mayor Brandon Johnson, a former labor organizer who was elected last year on a liberal platform, and who talks frequently about his own history of demonstrating. “We’re ready for this moment.”

In interviews, protest leaders described plans for days of peaceful gatherings that would draw thousands, perhaps even tens of thousands, of demonstrators to Chicago. Many of the protests will be focused on Israel’s military campaign in Gaza and on what activists see as complicity by President Biden and Ms. Harris in the killing of civilians there. The recent elevation of Ms. Harris to the top of the Democratic ticket has done nothing to quiet that outrage, many of them said.

“We came together and said, ‘Full steam ahead, nothing changes, all out for Chicago,’” said Hatem Abudayyeh, the national chairman of the U.S. Palestinian Community Network and a spokesman for a coalition of activist groups planning protests on Monday and Thursday.

Mr. Abudayyeh said he expected the crowds at his coalition’s marches to number well into the thousands, with protesters coming not only from the Chicago area, which has a large Palestinian American population, but also from across the region and country. Though the coalition includes more than 200 groups with a range of policy interests, including abortion rights, labor issues and climate change, Mr. Abudayyeh said he expected Gaza to be the primary focus.

Mr. Johnson said the city was happy to let demonstrators voice their concerns and insisted that the Chicago Police Department had been trained to facilitate peaceful marches. The mayor has repeatedly dismissed worst-case prognosticating based on the 1968 convention, though he said he was clear about potential risks.

Chicago police officers have been preparing for the convention for months, even inviting reporters recently to watch them train in riot gear, and the city has outlined a “coordinated multiple arrest policy” on its convention website. Officials listed “throwing things, breaking windows and destroying property” as actions that could lead to arrest, and noted that “obstructing traffic is not protected First Amendment activity.”

“I’ve led mass demonstrations in my life, and I can tell you the last thing that you want are detractors and deflectors within that space to try to come and hijack your message,” said Mr. Johnson. “So our responsibility is to make sure that people who mean our city and our country harm, that we weed out those.”

While Mr. Johnson was elected with support from many in the city’s activist community, some protesters have been critical of his administration’s approach to protests.

Mr. Abudayyeh’s group and other members of that coalition sued the city in federal court this year, arguing that its terms for a march were unacceptable. Though Chicago officials eventually agreed to let protesters gather within what they say is sight and sound of the United Center, the two sides remained at odds in recent days over the exact route the march would follow. The city’s proposed route comes within a few blocks of the arena, which sits about two miles west of downtown. On Friday, following a series of court filings, city officials agreed that protesters could have a stage and sound system.

Andy Thayer, a gay rights activist who is part of a coalition called Bodies Outside of Unjust Laws, which also sued the city, accused Mr. Johnson of being overly deferential to the Chicago Police Department.

“From what I’ve seen, he’s basically given the C.P.D. a total free hand, and this is a C.P.D. which has got a notorious record of disrespecting people’s rights — Chicago ’68 just being the most famous,” said Mr. Thayer, whose group eventually reached a deal to march on Sunday on Michigan Avenue.

Last month in Milwaukee, protests at the Republican National Convention were largely peaceful and smaller than organizers predicted.

Heading into the Chicago convention, there is disagreement among activists about how best to approach protests and whether to work through bureaucratic channels.

A leader of one group, Behind Enemy Lines, said its members disagreed with the goal of merely being “within sight and sound” of the arena in Chicago, arguing that protesters need to be “actively confronting the convention.”

“We think that their whole convention is illegitimate and criminal, and people should treat it that way,” said Michael Boyte, a co-founder of the group, which is critical of the U.S. government and describes itself as anti-imperialist.

Mr. Boyte said that his group, which is planning a protest outside Israel’s consulate in Chicago, does not encourage or plan for violence. But he said that protests should not be isolated in city-approved zones, and that protests often must be confrontational to gain attention.

While many of the protests taking place will be from the left of the Democratic establishment, one pro-Israel group, the Israeli American Council, is hoping to turn attention to the hostages who remain in Hamas captivity since the attack on Israel last October.

Elan Carr, the chief executive of the pro-Israel group, said it had also been frustrated with Chicago’s permitting process. If the council does not get the permit it is seeking, Mr. Carr said, it has an alternative plan: It has secured a private lot and is creating an exhibit to display on Tuesday bringing attention to the hostages and showing works by Israeli artists.

The city has also announced plans to make space in a small park near the United Center available for demonstrations. And it is possible that other groups or individuals who have not sought permission or announced their plans could turn up in Chicago.

Nicholas Sposato, a right-leaning Chicago City Council member from the Northwest Side, said in an interview that he worried that some protesters could be violent toward the police, and that it was possible protests could lead to “fisticuffs and arrests and rioting and looting.”

“I don’t know what these people are capable of,” he said.

Others in city government were less concerned. Walter Burnett Jr., whose City Council ward includes the United Center, said law enforcement had “given us assurance that they’re going to be able to handle everything”

“I’m not worried about the protests,” he said.

Still, the city has been preparing for the possibility of mass arrests. The Circuit Court of Cook County announced plans to open an extra court facility that will be available until midnight to process convention-related arrests, with some judges clearing their calendars to be able to assist.

Officials with the U.S. Secret Service, which will have command of the United Center and a hardened security area surrounding the arena, said they had worked with more than a dozen other agencies to develop plans for securing everything from the airspace above the United Center to traffic outside it.

The Chicago Police will be in charge of protests outside the security zone, and said they were prepared. The department’s leaders were also eager to stop hearing about 1968, pointing to a more orderly Democratic convention Chicago hosted in 1996.

“Oftentimes, it is forgotten that there was a Democratic convention between 1968 and now,” the police superintendent, Larry Snelling, said unprompted during a recent news conference. “It was a success.”

Robert Chiarito contributed reporting.

Mitch Smith is a Chicago-based national correspondent for The Times, covering the Midwest and Great Plains. More about Mitch Smith

Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs reports on national stories across the United States with a focus on criminal justice. He is from upstate New York. More about Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs

Advertisement