Alain Delon, Smoldering French Film Star, Dies at 88

The César-winning actor was an international favorite in the 1960s and ’70s, often sought after by the era’s great auteurs.

Supported by

Alain Delon, the intense and intensely handsome French actor who, working with some of Europe’s most revered 20th-century directors, played cold Corsican gangsters as convincingly as hot Italian lovers, died on Sunday. He was 88.

He died at his home in Douchy-Montcorbon, France, according to a statement his family gave to the French news service Agence France-Presse.

Hours later, President Emmanuel Macron honored him in a post on social media, saying, “Wistful, popular, secretive, he was more than a star: a French monument.”

During his heyday, the 1960s and ’70s, Mr. Delon was a first-tier international star, highly paid and often sought after by the era’s great auteurs.

When he burst on the scene in the gangster genre, as a sad-eyed, saintly young sibling in “Rocco and His Brothers” (1960), Luchino Visconti was in the director’s chair. Two years later, when Mr. Delon played a sexy stock trader, it was in Michelangelo Antonioni’s “L’Eclisse” (“Eclipse”).

And “Le Samouraï” (1967), released in the United States as “The Godson,” and the jewelry-heist flick “Le Cercle Rouge” (1970), in which Mr. Delon was a sinister, mustachioed ex-con, were both directed by Jean-Pierre Melville, patron saint of the French New Wave.

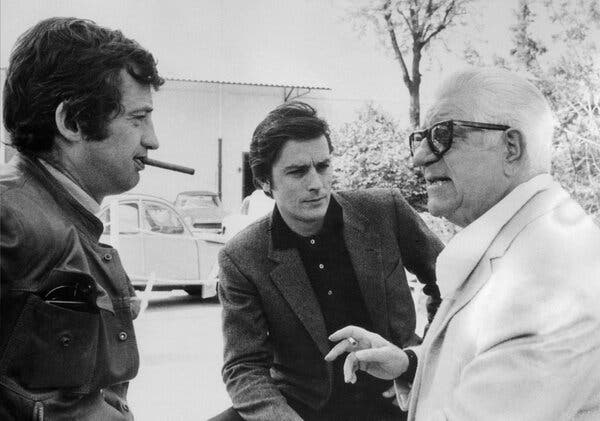

Louis Malle directed Mr. Delon’s segment of “Histoires Extraordinaires” (1968), based on three Edgar Allan Poe stories. In Jacques Deray’s “La Piscine” (“The Swimming Pool”), from 1969, Mr. Delon’s character rather casually murdered a houseguest. For the same director, he made “Borsalino” (1970), co-starring with Jean-Paul Belmondo as a Marseilles crime boss. Decades later, he appeared in Jean-Luc Godard’s “Nouvelle Vague” (1990).

Mr. Delon was well past the peak of his fame when he won the best actor César, France’s Oscar equivalent, for his performance as a middle-aged alcoholic grasping for happiness in the Bertrand Blier drama “Notre Histoire” (1984). That same year he played against type in a different way, as the sensual gay aristocrat Baron de Charlus in “Swann in Love,” drawn from Marcel Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past.”

Of course, his type depended on the audience’s point of view, and that seemed to vary from continent to continent. In Japan, he was considered a Western star, because of films like “Red Sun” (1971) with Toshiro Mifune. In Europe, he made a career of brutal crime dramas — as a cop killer, a hit man, an assassin, a murderer on the run — but he was enthusiastically accepted in other genres. He starred in the 1976 French best picture winner, “Mr. Klein,” as a wartime German art dealer threatened by being mistaken for a Jewish man with the same name.

American critics, however, often saw Mr. Delon only as a pretty boy. Vincent Canby’s New York Times review of “Le Samouraï” described his character as a “beautiful misfit” and faintly praised Mr. Delon as “doing what he does best (looking impassive and slightly tarnished).”

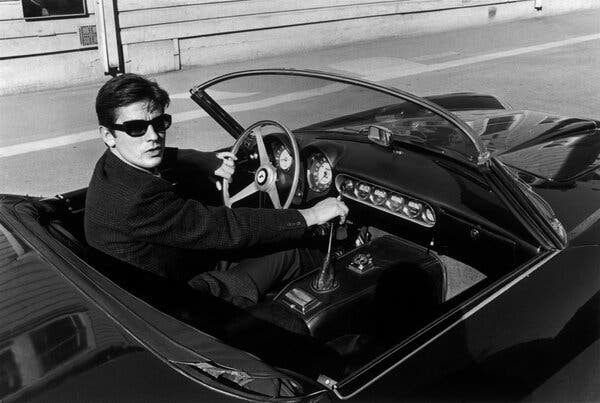

Yet Mr. Delon’s handsomeness was one reason his appeal endured. His “beauty has long inspired paroxysms of rapture,” Manohla Dargis wrote in April, when the art house Film Forum in Manhattan presented a retrospective series of 10 Delon films.

“This is, after all,” she added, “a star whose looks over the years have been described as sensual though also insolent, cruel, self-absorbed and androgynous, a word that helps explain why his beauty — as with that of other men whose looks threaten tidy gender norms — makes some viewers uneasy even as it sends others into ecstasy.”

Still, in 1965, Mr. Delon told the British magazine Film and Filming that shooting intimate physical contact was “a bore for me — love scenes, kissing scenes.” His explanation at the time: “I prefer to fight.”

But in 1970, when a reporter for The Times followed up on that question, he added, “I prefer to make love at home.”

Alain Fabien Maurice Marcel Delon was born on Nov. 8, 1935, in Sceaux, France, a wealthy suburb of Paris. His parents, Fabien and Édith (Arnold) Delon, divorced when he was 4.

Growing up, Alain had discipline problems and was expelled from several schools. The pattern seemed to continue when he joined the French Navy in his late teens. During his military service, which included the First Indochina War, he spent almost a year behind bars for various infractions, he said, before receiving a dishonorable discharge in 1956. One of his offenses, he told the talk show host Dick Cavett in 1970, was stealing a Jeep.

Then, in 1957, his life changed in a fairy-tale way. Having worked only at odd jobs (at one point he helped his stepfather, a butcher) and with no career plan, he happened to accompany a friend, the actress Brigitte Auber, to the Cannes Film Festival and was discovered there by a representative of the American film producer David O. Selznick. He was soon offered a contract — if he agreed to study English. But before he had a chance to pack his bags for Hollywood, he received another offer, from the veteran director Yves Allégret, and chose to stay in France.

Mr. Delon’s first credited screen role was that year in Mr. Allégret’s “When the Woman Meddles,” but it was his performance in René Clément’s 1960 film “Plein Soleil” (“Purple Noon”), based on the Patricia Highsmith novel and remade almost 40 years later in the United States as “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” that caught the public’s rapt attention.

He was Tom Ripley, a penniless but savvy young man hanging out with and taking revenge on rich, amoral friends. Mr. Delon’s onscreen image was arresting: sparkling blue eyes, mile-long lashes, sandy hair falling across his forehead, the pout, the slouch, the angelic demeanor that could shift instantly. He reminded many moviegoers of James Dean, the young American screen idol who had died five years before.

As Ms. Dargis wrote of Mr. Delon in April, his “stardom was sealed the moment Ripley peels off his shirt, baring his chest.”

Despite his rejection of Mr. Selznick, Mr. Delon was always forthright about his desire for Hollywood stardom, in addition to his international success. In 1965, he told The Los Angeles Times that he considered America “the top, the last step — it’s a kind of consecration.” But that dream never quite came true.

His first British film, “The Yellow Rolls-Royce” (1964), did well at the box office, but as just one face in that movie’s star-studded international ensemble cast, his Italian photographer-gigolo largely blended into the background. More than a half-dozen American films followed — including “Once a Thief” (1965), a crime drama in which he starred opposite Ann-Margret, and “Texas Across the River” (1966), a western spoof with Dean Martin — but none were hits.

For American moviegoers, Mr. Delon’s best-known film was probably “Il Gattopardo” (“The Leopard”), from 1963. Although it also starred Burt Lancaster, the film, based on a novel by the aristocrat Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, was an international production from Mr. Visconti.

Mr. Delon’s last effort was “The Concorde … Airport ’79” (1979). He played George Kennedy’s debonair co-pilot in a perpetually endangered SST.

In 1968, Stevan Markovic, a former bodyguard of Mr. Delon’s, was murdered and found in a dump near the star’s suburban Paris home. The investigation brought forth a scandal about alleged sex parties that involved both Mr. Delon and high-ranking political officials. Mr. Delon was questioned by the police, and an associate was indicted but not convicted; the case was never solved.

He was at home with controversy, making public statements that suggested homophobia and racism. The Daily Beast referred to his “well-known misogyny and problematic politics” in 2019, when he was given an honorary Palme d’Or, the Cannes Film Festival’s highest prize.

Mr. Delon was inducted into the Légion d’Honneur in 1991. For many years he was also a successful businessman, licensing his name to products.

He was married only once — to Nathalie Barthélémy (whose name at the time of their marriage was Francine Canovas) — from 1964 to 1969, but he led the life of a dedicated serial monogamist. He had enduring romantic relationships with women, including Romy Schneider, his frequent co-star, from 1958 to 1963; Mireille Darc, an actress and model, from 1969 to 1982; and Rosalie van Breemen, a Dutch model, from 1987 to 2002.

Survivors include a son, Anthony, from his marriage, as well two children from his relationship with Ms. van Breemen: a son, Alain-Fabien, and a daughter, Anouchka.

The three had been locked in a bitter feud over medical treatment for Mr. Delon, whose health had declined since a stroke in 2019.

Mr. Delon had denied paternity of a third son, Christian Aaron Päffgen — later known as Ari Boulogne — from a brief relationship with the pop star Nico. But Mr. Delon’s mother raised the boy as her grandson, giving him her surname from a remarriage. He died in 2023.

Most of Mr. Delon’s screen appearances in the 2000s were on French television, and he announced his retirement from film more than once. After an eight-year absence from movies, he turned up in Roman robes and a laurel crown as Julius Caesar in the historical farce “Astérix aux Jeux Olympiques” (2008).

His last feature film was a 2012 Russian-language comedy drama, “S Novym Godom, Mamy!” (“Happy New Year, Mommies!”), in which he played himself. He did the same in 2019, in “Toute Ressemblance,” a comic drama.

More important, perhaps, was the restoration and rerelease in 2021 of “La Piscine,” booked for two weeks at Film Forum, where it was so popular that it ran all summer. And new critics praised the film’s “unapologetic decadence” and Mr. Delon’s “sexy sleekness” and “hint of menace.”

He was often criticized for rampant egotism but seemed able to see fame for the complicated illusion that it was.

“This insanity gets to the point where ‘Delon’ becomes a label,” he said in a 1991 television interview, reported in The Connexion, a Monégasque news site. “And you must keep being it, play it, remain and dwell in it, because the public wants it, because you want it a bit and because that’s the rule.”

Aurelien Breeden contributed reporting.

Advertisement