OpinionGuest Essay

30 Years Ago, Two Young Strategists Cracked How to Beat a Guy Like Trump. Are Democrats Ready to Listen?

Supported by

Mr. Shenk is a historian and the author, most recently, of the forthcoming “Left Adrift: What Happened to Liberal Politics.”

Something in the Democratic Party’s subconscious knows that in times of change it should go to Chicago.

It’s the city where, in 1896, a 36-year-old William Jennings Bryan sent convention delegates into raptures by railing against Gilded Age plutocrats and urging Democrats to reconnect with their populist roots. It’s where Franklin Roosevelt announced the coming of a New Deal in 1932, starting a political revolution that pushed the Republican Party to the verge of extinction. It’s where the Roosevelt coalition ripped itself apart in 1968, with protesters and students brawling in the streets and delegates at one another’s throats. It’s where Bill Clinton went in 1996 to put the ghost of the ’60s to rest and build a bridge to the 21st century. And it’s where, next week, the party of Bryan, Roosevelt and Clinton will become the party of Kamala Harris.

But what is she going to do with it? Although Ms. Harris isn’t the kind of politician who dreams about sweeping transformations — “fancy speeches,” she says, aren’t her thing — she has a unique opportunity to set the course for Democrats as they stumble out of the Biden years, to outline the steps for beating Donald Trump this fall and renew the party over the next generation.

The easiest option will be to keep heading down the road Democrats have followed since Mr. Trump’s takeover of the G.O.P. eight years ago. This means piecing together an anti-MAGA coalition in a campaign defined by opposition to Mr. Trump while tacitly giving up on blue-collar voters who have moved toward the Republican Party. Although the track record of this program has been spotty — just ask Hillary Clinton — it has by no means been a disaster for Democrats. The Harris campaign chair, Jen O’Malley Dillon, summarized the logic in a memo detailing a path to victory shortly after President Biden left the race, arguing that Ms. Harris is poised to match his 2020 levels of support with nonwhite voters, young people and women, while improving on the party’s already strong performance with college-educated whites.

There’s another choice, a campaign dedicated to restoring the party’s frayed connection with the working class. This path is tougher to follow and could well be riskier in the short term because it requires providing a compelling reason to vote for Ms. Harris rather than against Mr. Trump. It’s also the plan with the best chance of building a lasting Democratic majority that could deal a hammer blow against Trumpism and pull American democracy back from the brink.

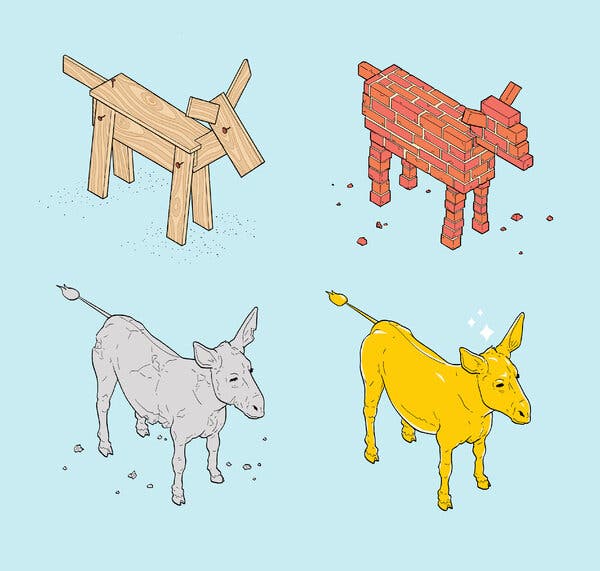

The key figures in this strategy are voters deeply skeptical of elites and alienated from both parties, usually because they lean to the left on economics but have cultural views closer to the center or the right. A political scientist might call them anti-system and ideologically cross-pressured, but you could also think of them as burn-it-down moderates. Politics doesn’t occupy much of their attention, in part because they probably didn’t graduate from college, which also means they’re more likely to come from the working or lower-middle class.

These voters have been moving away from Democrats since the 1960s. For most of this period, the group has been overwhelmingly white, but it has recently become more diverse, with Hispanic voters and younger Black men drifting away from their traditional partisan moorings under Mr. Biden, a phenomenon polls suggest Ms. Harris has not fully reversed.

It’s easy to assume that in a ferociously polarized electorate Democrats have no chance at winning back these voters in significant numbers. But polarization isn’t a force of nature, and party coalitions aren’t dictated by factors outside human control.

To understand how to break out of our current political stalemate, you have to look back at the last time Democrats came to Chicago with a nominee looking for a reset with the public and willing to wage an all-out war against polarization to get it. Bill Clinton was rewarded a few months later with a distinctly Rooseveltian coalition anchored in the bottom half of the income distribution — and with a victory on Election Day.

Ms. Harris still has a chance to assemble that kind of coalition. That makes it the perfect time to take a look at the strategy that made it possible almost 30 years ago.

Mr. Clinton’s campaign could have fallen apart on the day he accepted the presidential nomination in 1996. As he was huddled with staffers putting the final touches on his convention speech, news leaked that Dick Morris, his chief strategist, had kept up a long-running relationship with a prostitute. Clinton staffers were accustomed to what they called “bimbo eruptions,” but only when they came from the candidate. Mr. Morris was off the campaign within hours.

His departure left a vacuum that was quickly filled by Mark Penn and Doug Schoen, two longtime consultants who have become familiar characters in histories about the making of the modern Democratic Party. And by “characters” I mean “villains” — the pollsters behind the New Democratic push to abandon the working class, which spurred a populist revolt that gave the world President Donald Trump. Today, they are both frequent guests on conservative media who can be counted on to chastise Democrats for moving too far left.

But before rebranding themselves as pundits, Mr. Penn and Mr. Schoen were strategists with a reputation for winning tough elections. Unlike many operatives then or since, they approached campaigns with an overarching theory of politics in mind — a theory based in truths about the politics of polarization that Democrats are still wrestling with today.

The basic pieces of this framework came from Mr. Schoen, who witnessed the Roosevelt coalition breaking apart as a teenager in his hometown, New York City. Born during the prime of the postwar baby boom, Mr. Schoen had been raised in comfort on the Upper East Side. He was drawn to politics early and worked on campaigns that sent him into the city’s boroughs beyond Manhattan, where he saw racial and ethnic conflict feeding into a broader disaffection with liberalism among blue-collar whites. Neighborhoods like Brooklyn’s Sheepshead Bay were teeming with archetypal representatives of burn-it-down moderation. They were repelled by the orthodox conservatism of Barry Goldwater but also felt out of place in a Democratic Party that was making peace with the cultural upheavals of the 1960s, and they were looking for someone — anyone — who would speak for them.

Getting inside the heads of these kinds of voters became an obsession for Mr. Schoen. As a doctoral student at Oxford, he wrote a dissertation on Enoch Powell, a Conservative legislator, who stunned Britain in 1968 with a speech predicting that if current levels of immigration continued, soon “the Black man will have the whip hand over the white man.” After sifting through polls and election returns, Mr. Schoen convincingly argued that Powell drew millions of these voters to the right in the first election after his incendiary speech, shaking the foundations of British politics and setting the template for a new kind of right-wing populism.

Mr. Schoen came to believe that people were drawn to firebrands like Powell not just because they agreed with him on the issues, but also because he was saying something political elites had tried to keep out of public debate. It proved that he was in touch with a constituency that wasn’t being heard — and it gave his movement a frisson of excitement. You didn’t need a grass-roots campaign or a lavish advertising blitz to win over the public, just the right words and voters ready to hear them.

From that core understanding emerged the building blocks for a counterstrategy that Mr. Schoen took with him when he returned to the United States and struck up his partnership with Mr. Penn, whom he’d first met in school.

The pair started from the premise that public opinion is a fact. Ignoring a problem on the electorate’s mind doesn’t make it go away; it only sends voters searching for a candidate who will listen. Views can shift over time, but probably not over the course of a campaign. Elections aren’t a battle for hearts and minds. They’re a fight to give voters what they already want.

Mr. Penn and Mr. Schoen believed that the culture wars had killed off the New Deal coalition and given conservatives a durable advantage at the polls. “Democrats must face a hard truth,” Mr. Schoen argued in a memoir published in 2007. “We do not have the natural majority coalition in American politics.” They would have to grind out victories by holding the middle ground in a battlefield that favored Republicans.

Mr. Clinton gave Mr. Penn and Mr. Schoen an opportunity to test this strategy on a national level when he brought them on to his re-election campaign. The president was coming off the brutal 1994 midterms, where Republicans won control of both the House and the Senate for the first time in 40 years. Working alongside Mr. Morris, the men came up with a plan for resurrecting Mr. Clinton in time for re-election. “The perception across America was that Clinton was a liberal,” Mr. Schoen recalled. “Our first task was to change that.”

They homed in on two slices of the electorate, referred to inside the campaign as “Swing 1” and “Swing 2.” Swing 1 consisted of voters who leaned to the right on economics and to the left on culture, chiefly middle- and upper-middle-class suburban women. (Mr. Penn called them soccer moms, popularizing a term that was already in circulation.) Swing 2 voters were the latest version of the burn-it-down moderates. Blue collar and disproportionately male, they were hostile to Washington and uncomfortable with social change. Many had supported the businessman-turned-politician Ross Perot in 1992, a fact Mr. Penn knew well, because he had done early polling for Mr. Perot.

Mr. Penn and Mr. Schoen saw the fight for the center as a two-front war, and they workshopped messages intended to win over both of their target groups — measures against teen smoking for Swing 1, tough talk on trade for Swing 2; stronger environmental regulations for one, strict border controls for the other. They coupled small-scale initiatives including school uniforms with a push to the center on the big-ticket issues of the campaign: for balancing the budget while protecting Social Security and Medicare, in favor of strong families but opposed to dragging the country back to the 1950s.

Although soccer moms would be remembered as the secret to Mr. Clinton’s victory, the campaign tried to have the best of both worlds, holding on to the party’s working-class base while making inroads with the affluent. Mr. Clinton did well in traditionally Republican suburbs and broke records for Democrats with college-educated whites, but he did even better among noncollege whites, and he was the last Democrat to turn in a stronger performance in West Virginia (one of the poorest states in the country) than in California (one of the wealthiest).

Mr. Clinton didn’t get the thoroughgoing vindication he wanted. With Mr. Perot in the race, he didn’t win a majority of the popular vote, coming in just short, with 49.2 percent. Republicans retained control of Congress and added two seats in the Senate. Barely half of eligible voters cast a ballot, the lowest turnout since the 1920s. But it was, despite all the caveats, a place to build — a sign that Democrats could still repair their damaged relationship with working people.

Yet it didn’t happen quite as Democrats hoped. Part of the blame goes to Mr. Penn and Mr. Schoen, who after winning a hard-fought race for voters up and down the economic scale pushed the Democrats to abandon economic populism altogether, with the hope of extending Democratic gains even deeper into the middle and upper classes.

Mr. Clinton’s own failures contributed, too. The Monica Lewinsky scandal put a damper on the bid to reclaim family values for Democrats over the short run, and the fallout from the administration’s policies over the long run was even worse: Free trade hollowed out the heartland, lax financial regulations helped inflate bubbles on Wall Street and Democrats failed to stem organized labor’s ongoing decline.

The stage was set for a revolt when the economy turned south, which it did just in time for outrage with the agonizingly slow recovery to be directed at the country’s first Black president. Like Mr. Clinton, Barack Obama minimized the damage to himself by keeping the concerns of burn-it-down moderates front and center when his own campaigns were on the line, running on a platform that mixed bread-and-butter economics with a moderate position in the culture wars. But Democrats treated the decidedly mixed electoral record of the Obama years — two devastating midterms, a relative squeaker of a re-election — as proof that inexorable demographic changes were ushering in a progressive realignment. When combined with an incumbent’s natural defensiveness about the status quo, along with the unique blend of incredulity and disgust that Mr. Trump brings out in Democrats, the party was left blindsided by the appeal of a candidate who said America wasn’t already great.

There was no better indicator of the shifting mood since the Bill Clinton years than the Hillary Clinton campaign. Staking her presidential ambitions on the emerging Democratic majority, she gambled on running up the score with Swing 1 and cast Swing 2 into the basket of deplorables. That seemed like a good bet, right up until the votes were counted.

Matters didn’t improve much with Scranton Joe Biden at the top of the ticket. Although blue-collar whites moved slightly back toward Democrats in 2020, Mr. Biden’s biggest gains came with college-educated whites, and those were almost offset by significant losses of Hispanics and a slight downturn among Black Americans.

Under Mr. Biden, Democrats landed on a twofold strategy for stanching the party’s bleeding of working-class voters — and keeping Mr. Trump from setting foot back in the White House. Bidenomics was meant to stamp out Trumpism at its roots by putting the interests of working Americans first while checking boxes on progressive wish lists. It was populism as seen through the eyes of an Elizabeth Warren staffer, with a clear plan of attack for how to drive down carbon emissions while boosting employment, but not much to say on the unfolding fiasco at the border. Meanwhile, Democratic political operatives took the fight directly to Republicans, running campaigns that focused almost entirely on the scourge of Trumpism, while emphasizing abortion rights and promising, vaguely, to protect democracy.

The two halves of the strategy never really cohered. While policymakers in Washington were trying to win blue-collar votes, Democratic strategists were doubling down on suburbanites. A healthy economy might have papered over those contradictions. Instead, sticker shock at the rising cost of living soured voters on the economy, with good reason. Real wages tumbled and interest rates soared during Mr. Biden’s first two years in office — a stark contrast with the growing paychecks and cheaper mortgages in the middle of the Trump years.

Pointing to Mr. Biden’s historic support for organized labor did little for the 94 percent of private-sector workers who aren’t in a union, and the administration’s signature legislative achievements — $1.6 trillion in new expenditures, much of which is still waiting to be rolled out — didn’t address the concerns of voters trying to make ends meet now. Passing most of the last year in denial about the landslide majority of voters who thought Mr. Biden was too old for the job made an already difficult task close to impossible.

Mr. Trump’s campaign was engineered from the ground up to take advantage of this opportunity, running an operation intended not just to turn out blue-collar and rural whites but also to bring young men of color into the Republican Party for good. Swapping Ms. Harris for Mr. Biden has scuttled talk about a realignment, but the polls are still close enough that a second Trump presidency is just a coin flip away.

Democrats trying to avoid this fate won’t be dusting off the old Bill Clinton playbook, and that’s not a bad thing. Mr. Penn and Mr. Schoen’s assumption that Republicans were the dominant party no longer holds. Public opinion on issues ranging from gay rights to abortion to labor unions has shifted to the left. Self-identified liberals are a somewhat higher percentage of the electorate — 26 percent today, compared with 16 percent in 1996 — and a much stronger force in the Democratic Party.

But even if the country has changed, the laws of political gravity haven’t been repealed. That means there are still lessons to be learned from a Democratic president who knew how to get working-class votes.

The first turns on how you promise to govern. Like most voters, working Americans want to see tangible improvements in their daily lives. Structural reforms to rein in corporations and increase worker power are worthy goals, but the most important question in presidential politics is still Ronald Reagan’s “are you better off than you were four years ago?” With Bidenomics, Democrats were casting their eyes too far forward, promising reforms that have not trickled down to enough of the country. No financial adviser would say that maxing out contributions to your 401(k) justifies skipping the electric bill. Ms. Harris can’t simply campaign on finishing the work of Build Back Better. Instead, she needs to offer a credible program for driving down the cost of living.

The second is how to pick your battles in the culture war. Abortion rights are one of the strongest weapons in the Democratic arsenal today. But it’s worth pausing to think about why. When Democrats watch Mr. Trump move to the center on abortion, they recognize that he’s trying to take the sting out of an issue that has done enormous damage to Republicans — and they know that his embracing an extreme position, like banning I.V.F., would be a gift to his enemies.

The trick for the left is to think about the politics of other hot-button subjects in the same way they do abortion. It pays for Democrats to hold their ground when public opinion is on their side, but that’s not always the case. When the polls are against them, it pays to look for the middle ground. On immigration, for example, this means an unapologetic defense of the bipartisan border security bill Mr. Trump torpedoed earlier this year, and then asking Republicans how their proposed system of migrant detention camps is going to work.

This raises the last, and most important, lesson from Mr. Clinton’s 1996 campaign: It’s the policies, stupid. Voters don’t spend their free time sifting through white papers, but they come by their opinions honestly and won’t be talked out of them quickly. They aren’t drones waiting to be told what to think, and they won’t be tricked by clever marketing or viral memes.

The Harris team has gotten off to a strong start in the messaging wars. The vibes, for the first time in a long time, are great. But Republicans live to kill Democratic vibes, and they have a tested strategy for doing it — which, in this case, means turning Ms. Harris into a San Francisco liberal who will open the border, defund the police, cackle while prices go through the roof and only got the job because of … well, you know.

If Ms. Harris wants to persuade skeptical voters that she will turn the page, she needs to prove it with policies that address the problems they care about most. And if Democrats want to convince Americans that Republicans are weird, they can’t just count on Tim Walz being adorable on TikTok. They need to show they’re the normal ones — a party for working families that’s filled with people who love this country so much that they know it can be even better.

“We have a solemn responsibility to honor the values and promote the interests of the people who elected us,” Mr. Clinton said in his first weeks as a presidential candidate. He didn’t hold up his side of the bargain, and Democrats are still living with the consequences. But these goals — honoring values and promoting interests — should be watchwords for Democrats trying to win back lost ground with the working class.

Although the choices Ms. Harris makes in the next few months will be crucial, this effort can’t be left to a single campaign. It will take a movement with a consistent vision supported by candidates up and down the ballot who deliver on their promises after taking office. All the better if those candidates look and sound like the people they want to represent, rather than the latest model to roll off the Ivy League assembly line.

There’s no denying that the odds against this project succeeding are long. But it would create a country where ordinary people had more — a great deal more — say over their lives. Another name for that is democracy.

Don’t you want to see what it looks like?

Tim Shenk (@Tim_Shenk) is a historian and co-editor of Dissent magazine. “Left Adrift,” which comes out in October, is a history of the rivalry between Doug Schoen and the strategist Stan Greenberg.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, WhatsApp, X and Threads.

Advertisement